The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: Herring River, Wellfleet

Cape Cod Life / November/December 2017 / History

Writer: Christopher Setterlund / Photographer: Paul Rifkin

The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: Herring River, Wellfleet

Cape Cod Life / November/December 2017 / History

Writer: Christopher Setterlund / Photographer: Paul Rifkin

Editor’s note: This is the 18th in a series of articles covering the region’s dramatically changing coastline. Click here to see all of the articles.

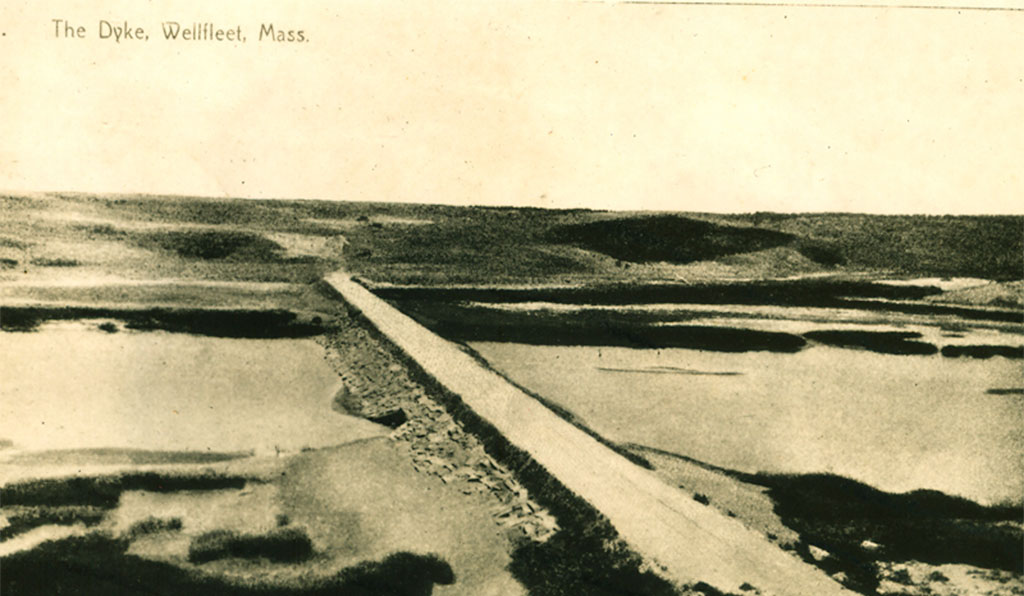

Wellfleet Harbor, the Herring River and the Chequessett Road dike.

“The Herring River Restoration Project is a rare opportunity to reclaim a once-vital lost ecosystem. . . It is the result of more than a decade of careful study and collaboration involving Wellfleet, Truro, the National Seashore and other state and federal agencies.”

Throughout history the tides at Wellfleet Harbor carried oxygen-rich ocean water up the six-mile long Herring River. In the last century, however, a manmade dike has disrupted the natural flow of the tides and is threatening the ecosystem. Here, we examine changes at the Herring River and the efforts being made to restore the surrounding area to its former thriving glory.

For more than 2,000 years the Herring River was surrounded by a 1,100-acre salt marsh. According to Don Palladino, president of Friends of Herring River, the river was the center of Wellfleet’s community and economy as recently as 120 years ago.

“Town reports from the late 1890s indicated that 200,000 herring were netted annually from the river,” Palladino says. “Today our herring counters register 10 percent of that number.”

In the early 20th century came an idea to build a dike across the Herring River on Chequessett Neck Road. The intention was to reclaim the marsh area around the river, create cranberry bogs, increase shellfish breeding, and lessen the mosquito population. The project was approved at a town meeting in April 1908 with $10,000 earmarked for construction, and was completed in September 1909.

John Portnoy, a retired Cape Cod National Seashore ecologist and co-author of the 2016 book “Tidal Water: A History of Wellfleet’s Herring River,” shares more reasons why the dike was built.

The map in the top right shows the extent of the historic salt marsh (in tan) compared with the extent of the salt marsh today (black). Tidal restriction has reduced the marsh from approximately 1,000 acres before installation of the dike to about 10 acres today. The aerial photograph in the background shows the Herring River and marsh, with Wellfleet Harbor in the foreground.

“By the late 19th century, the resources of Cape Cod Bay had been severely over-harvested, reducing the tidal wetlands’ economic and social values,” Portnoy says. “In addition, deforestation and sheep grazing caused soil run-off into the Herring River and its tributary creeks, making them no longer navigable.” These lost values, plus a chronic mosquito nuisance, made it easy to convince town residents to dike the river, Portnoy explains.

The dike reduced the opening of the river from 450 feet to approximately 18 feet, severely cutting down on the oxygen-rich water flowing into the salt marsh. It also blocked the sediment carried upstream, which had allowed the salt marsh to grow and thrive. Subsequently the marshland has receded, with only 10 acres remaining today.

Tim Smith, restoration ecologist at the Cape Cod National Seashore and a member of the Herring River Restoration Committee, says the negative effects of the dike were not known at the time it was built.

“People back then thought they were doing the right thing,” Smith says, “but we’ve since learned how important tidal wetlands and estuaries are regarding coastal fisheries, water quality, wildlife, nutrient and carbon cycling, recreation, and the character of small seaside towns.”

By 1971 the original tide gates of the dike had deteriorated. Larger amounts of seawater had begun seeping north of the dike, which had become a freshwater ecosystem, laying stagnant and occasionally flooding areas of the Chequessett Golf Course. The idea of a potential restoration of the river was debated at that time. Instead the state approved and partially funded rebuilding of the dike in 1974. The rebuilt dike is now more than four decades old and deteriorating again.

The extensive damage to the salt marsh caused by the dike has also had a more subtle influence on the surrounding area, according to Portnoy.

“When water drains from normally water-logged salt marsh peat, it sinks like a dried-out sponge,” he explains. “Portions of the Herring River flood plain have sunk two to three feet since the dike’s creation. This greatly compromises the coastal wetland’s ability to protect nearby upland properties during storm surges.”

A vintage photo of the dike. Courtesy of the Wellfleet Historical Society

The drying out of the peat has contaminated the surrounding water, Palladino says, observing, “The acidity in some portions of the Herring River is comparable to a lemon, which is unhealthy for fish.” In 1985 the river area north of the dike was closed to all shellfishing due to bacterial contamination of the water.

In 2005 the Town of Wellfleet and Cape Cod National Seashore began discussions about whether restoration of the Herring River was possible. Truro joined in the restoration plan as well in 2007. These discussions resulted in the Herring River Restoration Project.

“The Herring River Restoration Project is a rare opportunity to reclaim a once-vital lost ecosystem,” Palladino says. “It is the result of more than a decade of careful study and collaboration involving Wellfleet, Truro, the National Seashore and other state and federal agencies.”

Palladino says the project will include replacing the existing Chequessett Neck Road dike with a new bridge and tide gates, installing a Mill Creek dike and tide gates, elevating Pole Dike Road, and installing culverts and tide gates, removing the portion of High Toss Road that blocks tidal flow, and completing flood protection measures at Chequessett Yacht and Country Club and specified private properties.

The project would be the largest tidal restoration project undertaken in the Northeast United States, Portnoy says.

Leaving the dike in place would be detrimental. “If nothing changed, the marshes would continue to disappear,” Portnoy says, and “the estuary would continue to be a major source of mosquitoes and greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane.”

Palladino agrees. “Doing nothing continues to put the community and environment at risk. Without the project, we can expect all of the damage caused by tidal restriction to continue or worsen,” and that would lead to “closure of shellfish beds downstream of the dike, potential for fish kills due to poor water quality, and loss of the river’s herring habitat.”

“Maintaining the status quo is not a viable option,” Smith adds, noting that conditions in the river continue to degrade and if the dike remained in place, without proper maintenance, the tide gates will ultimately fail, causing sudden flooding for upstream properties.

“Herring River, once a jewel of the Outer Cape, is in serious distress,” Palladino says. “We have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to recreate a natural tidal wetland system that we lost due to human actions, and if we fail to act, these conditions will persist and likely worsen over time.”