Handcrafting history

Cape Cod Life / July 2018 / Art & Entertainment, People & Businesses

Writer: John Greiner-Ferris / Photographer: Teagan Anne

Handcrafting history

Cape Cod Life / July 2018 / Art & Entertainment, People & Businesses

Writer: John Greiner-Ferris / Photographer: Teagan Anne

David Lewis’ statue of President John F. Kennedy is displayed prominently in front of the JFK Museum in Hyannis.

Sculptor David Lewis finds redemption in art

Like many histories of families on Cape Cod, Osterville sculptor David Lewis’ family history is a curious blend of lore and real memory handed down through the generations. An interesting detail is that the Lewis family insists their ancestors arrived on Cape Cod—not on the blue-blooded Mayflower, but on the unmemorable second ship. There’s no denying the Lewis family roots run deep on Cape Cod, and deep roots that cling tenaciously to this sandy peninsula, roots that do not let go, are what are needed to endure when storms rage in off the Atlantic, or into your life. Ultimately, it was his roots in the Osterville community, and a wife who never gave up on him, that kept Lewis from washing out to sea, and ultimately allowed him to become one of the most sought-after sculptors on the Cape.

For Lewis, the past—his immediate past—starts on a 32-acre family farm that’s no longer in the family, on which his father, John, was born in 1907. During the Depression, his grandfather sold the farm for $5,000, and today it’s conservation land, the Town of Barnstable having bought it to deter development.

Lewis was born in 1941, the third of four children. In school, he was co-captain of the football team. The only artistic quality he displayed at the time was the ability to draw better than most of the other students. For three years after high school, Lewis worked as a deckhand on the research vessel Atlantis out of Woods Hole, taking summers off. Summer on Cape Cod meant sunshine and girls, so why give that up, he thought. “Port Captain Pike knew I would do the work and wouldn’t mess around in port, so he’d keep hiring me even though I took summers off,” Lewis says.

He would lifeguard on Craigville Beach during the day and then hit the town at night. One night, at the Vet’s Club in Hyannis, he met a young woman from Columbus, Ohio, a student at Ohio State University. She had heard about the sun and the beaches and the boys of Cape Cod and got herself a summer job as a maid to see it firsthand. “We had a standing date on Tuesday,” he says. “I got paid on Friday, but by Tuesday I was broke, and Tuesday was the day she got paid.” Based on that tenuous arrangement, the two developed a relationship, and Lewis proposed marriage to Nancy before she returned for her final year of college.

They married in 1964, he got his master’s license in plumbing—following in his father’s footsteps—and they had four kids—three girls and David Jr., born on Guam, who they adopted when he was six weeks old. He died at age 39 from a heart attack. “From too great a distance I watched my son become the man he became,” Lewis recalls.

Lewis hated plumbing, though he was successful—he had several crews working for him and even had a side business with a truck delivering heating oil. Things just weren’t right, and by 1977 he and Nancy had split up for the fifth time. The breakups were caused by his drinking.

As with many human endeavors—businesses, marriages, life in general—either something changes, or the thing dies. Nancy told him that if he didn’t join Alcoholics Anonymous, she was going to leave him for good. So he joined AA. And he hated it. He hated it worse than plumbing.

“A buddy would take me around to meetings and I’d think, what a bunch of losers,” Lewis recalls. But AA was the best thing that happened to him, he says. AA made him face the truth about himself, good and bad, and while there was a lot of bad—he had caused hurt and suffering to people he loved—the good was he found the truth about himself: He wanted to be a sculptor.

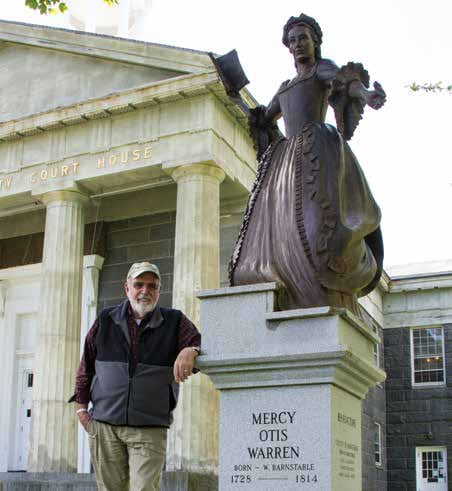

Lewis proudly poses beside his statue of noted American revolutionary Mercy Otis Warren, displayed outside of the Barnstable County Courthouse.

To this day, he still has no idea how sculpting took root in his mind. A friend, Teddy Crosby—“Gunther” to his friends—of Crosby Boatyard fame, had some chisels and a block of mahogany lying around that he gave to Lewis. His first sculpture was of Christ’s head, and for the next decade or so, instead of spending nights in The Fox Hole, Lewis would head out into his backyard to a 10-by-12-foot shed and work on small carvings. During those years, for more times than he can remember, he’d see the sun come up, having spent the night carving.

His big break came in 1984 when Monsignor Ronald Tosti, who had been his pastor at Our Lady of the Assumption, was forming a new parish, Christ the King, in Mashpee. Monsignor Tosti was intrigued to hear that Lewis was sculpting, because his vision for the new church was that local artists would make all of the artwork in the church. Monsignor Tosti asked Lewis if he’d ever done anything life-size, and even though he hadn’t, Monsignor Tosti still commissioned him to carve statues of Jesus and St. John the Baptist. “I was happy to give him a chance,” Monsignor Tosti says. “I watched David go through various stages of faith, and a lot of what he did was based in his faith.”

The project pushed Lewis to his limits. At one point, he stopped working for a month, overwhelmed. Monsignor Tosti stuck with David, and it took him 46 months to finish the statues that are still on display in the church.

During the Christ the King commission, Lewis developed asthma, the dust from carving and sanding exacerbating his condition, so he turned to bronze. At the same time, Lou Cataldo entered his life. Cataldo, who died in 2015, was a force of nature in Barnstable County, someone who could get things funded and done. Along with the many public service roles he played, including deputy sheriff, Cataldo was the county archivist. Cataldo became Lewis’ Medici, believing in him and commissioning him to make four historical sculptures—the statues of American revolutionaries Mercy Otis Warren and James Otis on the Barnstable County Courthouse lawn, and the statues of the Native American Iyannough and John F. Kennedy in Hyannis—which have defined Lewis as a preeminent local sculptor and cemented his career.

The two Otis statues are monumental, set high on pedestals on a hill, removed from the viewer. Inspired by a painting in the Massachusetts State House, the James Otis statue faces forward, but Mercy is slightly turned and taking a step up, indicating the rise of women, Lewis says. Upon closer inspection, both statues are surprisingly detailed. Mercy’s bodice is intricately detailed and her flowing drapery is highly textured. James’ coat is roughly pockmarked, his socks striated, his pantaloons a series of crosshatches.

By comparison, the statues of Iyannough and JFK are less detailed but more human in scale. Iyannough sits easily on a rock holding a pipe, gazing serenely into the viewer’s eyes. In JFK we see not the president but a man, barefoot, wearing a polo shirt and a wedding ring, a detail that Nancy wanted included. His khakis are rolled up as he strides through the sand, his eyes focused on something far off. “I like life-size because you can identify with the person,” Lewis says, probably not realizing how weighted his words might be, having had to find and identify the person inside himself, too.

Lewis has now been sculpting—and sober—for 40 years. His 40 years of sobriety have taught him to savor moments in life he knows he might have otherwise missed. He’s 76, but now is not the time to slow down. He’s got a lot of time to make up, and a lot of friends to pay back: Captain Pike, Gunther, Monsignor Tosti, Lou Cataldo, and especially Nancy. And what if he were commissioned to make a statue of David Lewis? What would it look like? “It would be life-size and human and the best I could do for David Lewis,” he answers. “That’s about it.”

To see David Lewis’ work, including his smaller sculptures, visit the Osterville Art Gallery, 8 West Bay Road, Osterville, davidlewissculpture.com/osterville-art-gallery.