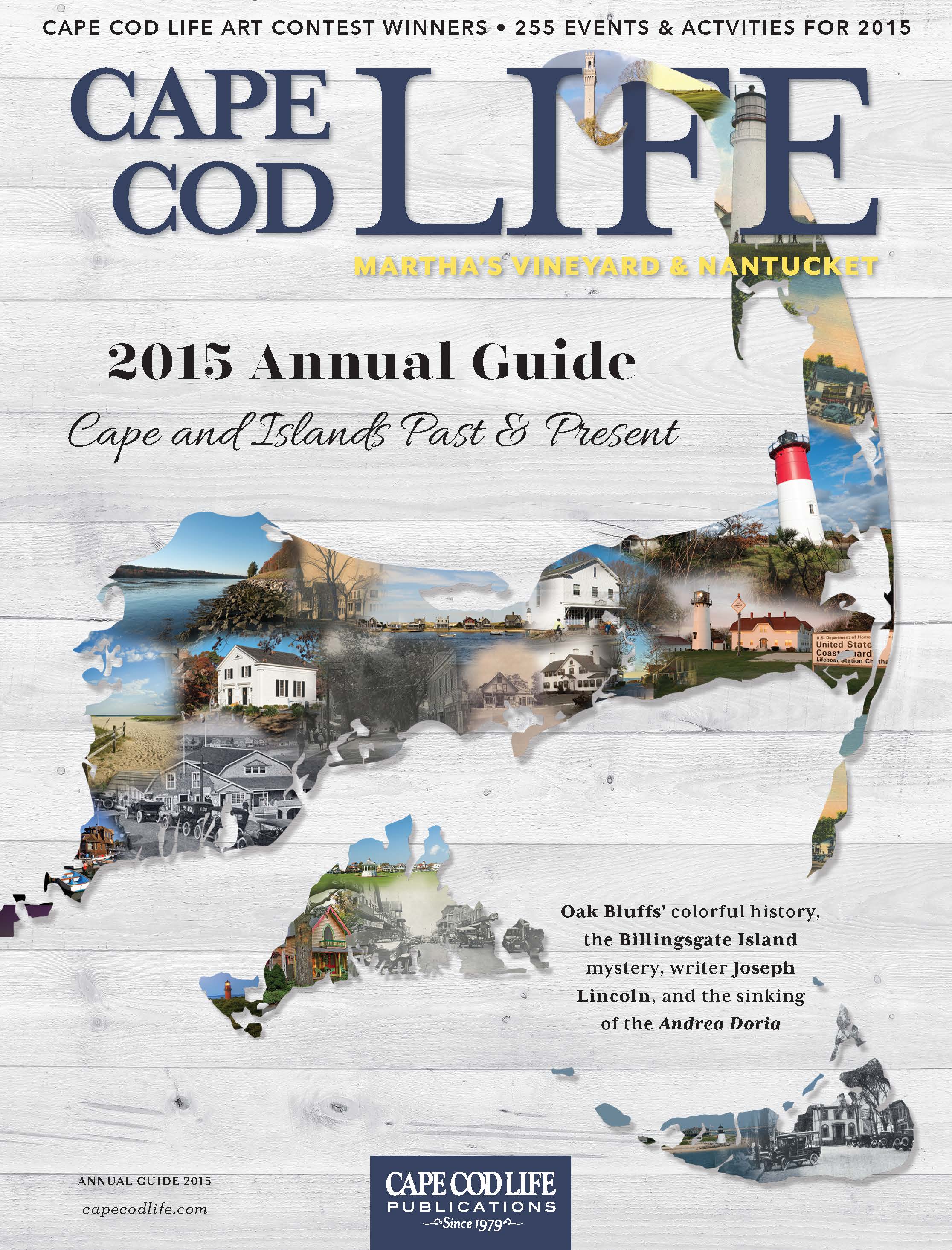

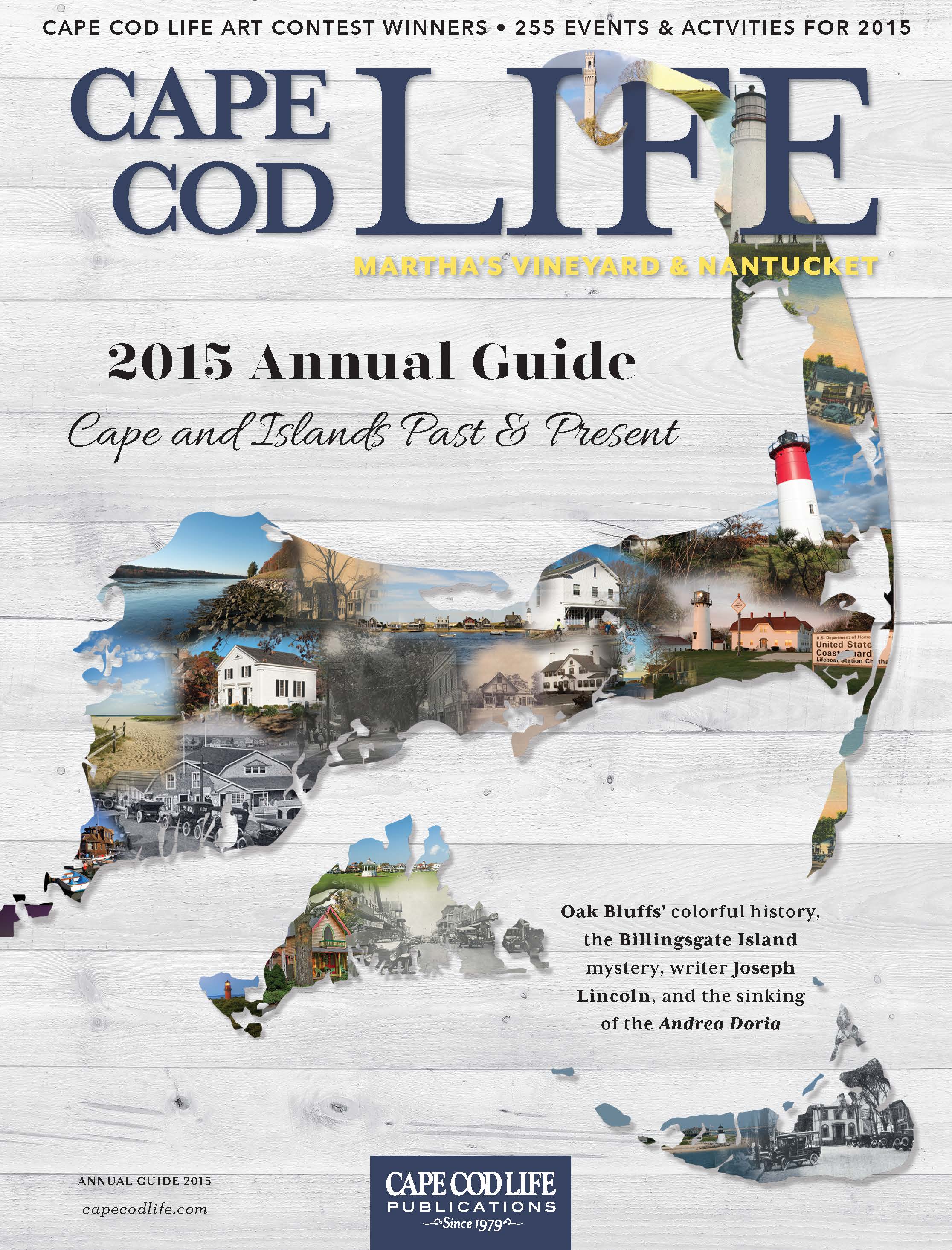

Homeport – Centerville

Cape Cod Life / Annual Life 2015 / History

Writer: JP Pochron

Homeport – Centerville

Cape Cod Life / Annual Life 2015 / History

Writer: JP Pochron

In an era dominated by shipping, many captains called this Barnstable village home.

Thedy Crosby had signed on to a ship due to sail out of Centerville. The ship lay anchored in the harbor waiting for one crewmember. Thedy had changed his mind. He did not want to go aboard so instead, he hid in a barn. His father found him, though, and marched him to the waiting ship. Thedy’s first voyage took him around Cape Horn. He never went to sea again.

Thedy Crosby’s story—as told in Florence Windship Ungerman’s Long Beach: Then and Now—is the opposite of that of many boys in Centerville from about 1820 to soon after the Civil War, when life in the Barnstable village was inextricably tied to the sea. Many of these youngsters, whether eager or reluctant at the outset, went to sea as cooks or cabin boys and eventually worked their way up to captain.

Arthur Scudder Phinney was one of these. In 1836, Phinney earned $37.20 working as a cook for six months aboard the sloop, Glide. He was 14 years old. By the time he was 30, Phinney was captain of the schooner, George W. Whistler, Jr., which carried general cargo to Albany, New York.

In his career, Phinney would travel the seven seas and serve as master of four vessels including the barque, Charles P. Mowe. While in the Mediterranean during the 1850s, it is said he was captured by Turkish soldiers and imprisoned. It may be viewed as ironic, then, that after all the challenges, trials, and storms he weathered in a ‘round-the-world sailing career, Phinney lost his life in 1871 when his small sloop, traveling from New Haven, Connecticut with a cargo of oysters, sunk off the coast of Cotuit, a few miles from his Centerville home on Park Avenue.

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

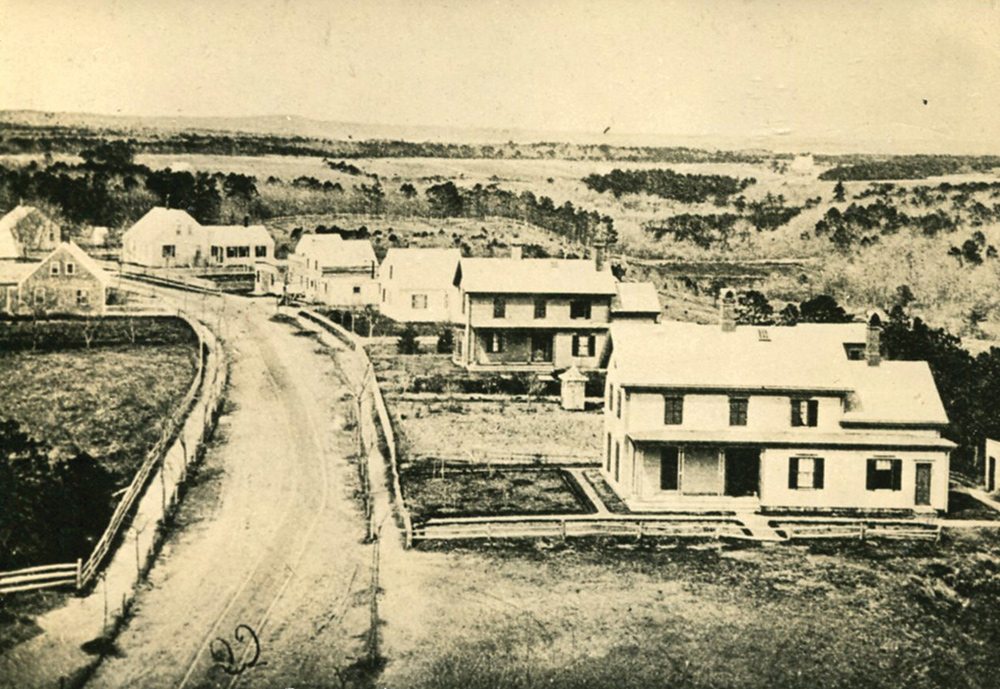

Originally called Chequaquet, Centerville, located close to Hyannis on the Cape’s Nantucket Sound side, was established near Chequaquet’s Great Pond (Lake Wequaquet). The most centrally located of the town of Barnstable’s seven villages, it was called Centreville; the spelling was changed to ‘Centerville’ circa 1834, when the village’s first post office was built. The building remains on Main Street today, and over the years it has been home to many businesses.

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

By the 1820s, the center of the village shifted to the sea as maritime trade became a vital part of Cape Cod life.

Growth coincided with the success of the coastal and deep water trade. Young boys from the village got an early start in the shipping business—often as cooks’ helpers.

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

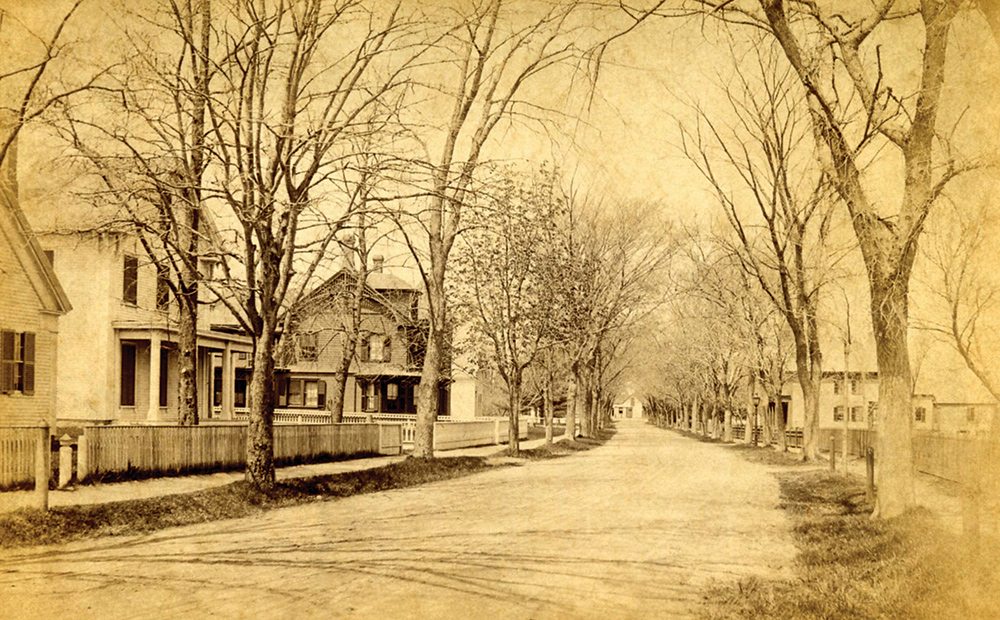

During this era, Centerville was home to more than 100 shipmasters; most were coastal trade captains, while 25 captained deep water vessels, which transported goods internationally. Approximately 50 of these men built homes on Main Street and its vicinity. Some of these homes are still there today; even with alterations made over the years, the grand originals are recognizable.

Artwork by Josiah Richardson

Russell Marston was another youngster who got an early start in the shipping industry; at 9 years of age, he began his career at sea as a cook and cabin boy, earning just $3 a month. By the time he was 30, Marston owned and commanded the Centerville-built coaster, Outvie.

Like other Centerville shipmasters that returned to the village to begin second careers in farming, fishing, cranberry cultivation, or business, Marston was ready for a new career by the time he was 31. He foresaw the death knell of the coastal trade and in 1847, docked his boat in Boston and, using the seaman’s “for sale” sign, tied a broom to the ship’s masthead. Marston invested the proceeds from the sale in a food shack. That investment eventually led to the establishment of an elegant and popular restaurant in Boston: Marston’s Restaurant on Brattle Street.

Marston abhorred injustice and took a stand as an abolitionist, even at the cost of his business and social opportunities. At one time, Marston’s Restaurant was the only business place of its kind in Boston that was open to black patrons. Famed abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, was a friend whom Marston greatly admired. He named his daughter, Helen Garrison Marston.

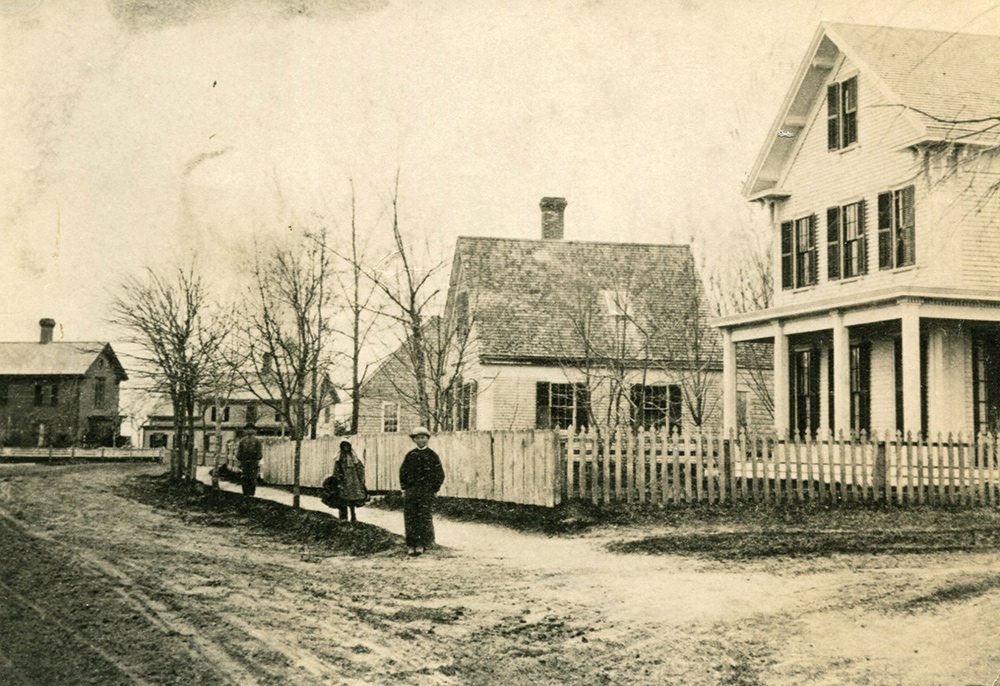

Marston continued, however, to call Centerville home. His absence was lamented at the village’s ‘Home Week’ celebration in 1904. Marston, 87 at the time, was unable to attend because of a business engagement. The booklet published to commemorate the festivities noted that the average age of the 14 oldest persons in the village at the time was 84. Marston’s home at 454 Main Street has undergone revisions over the years but is still recognizable from early photographs.

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

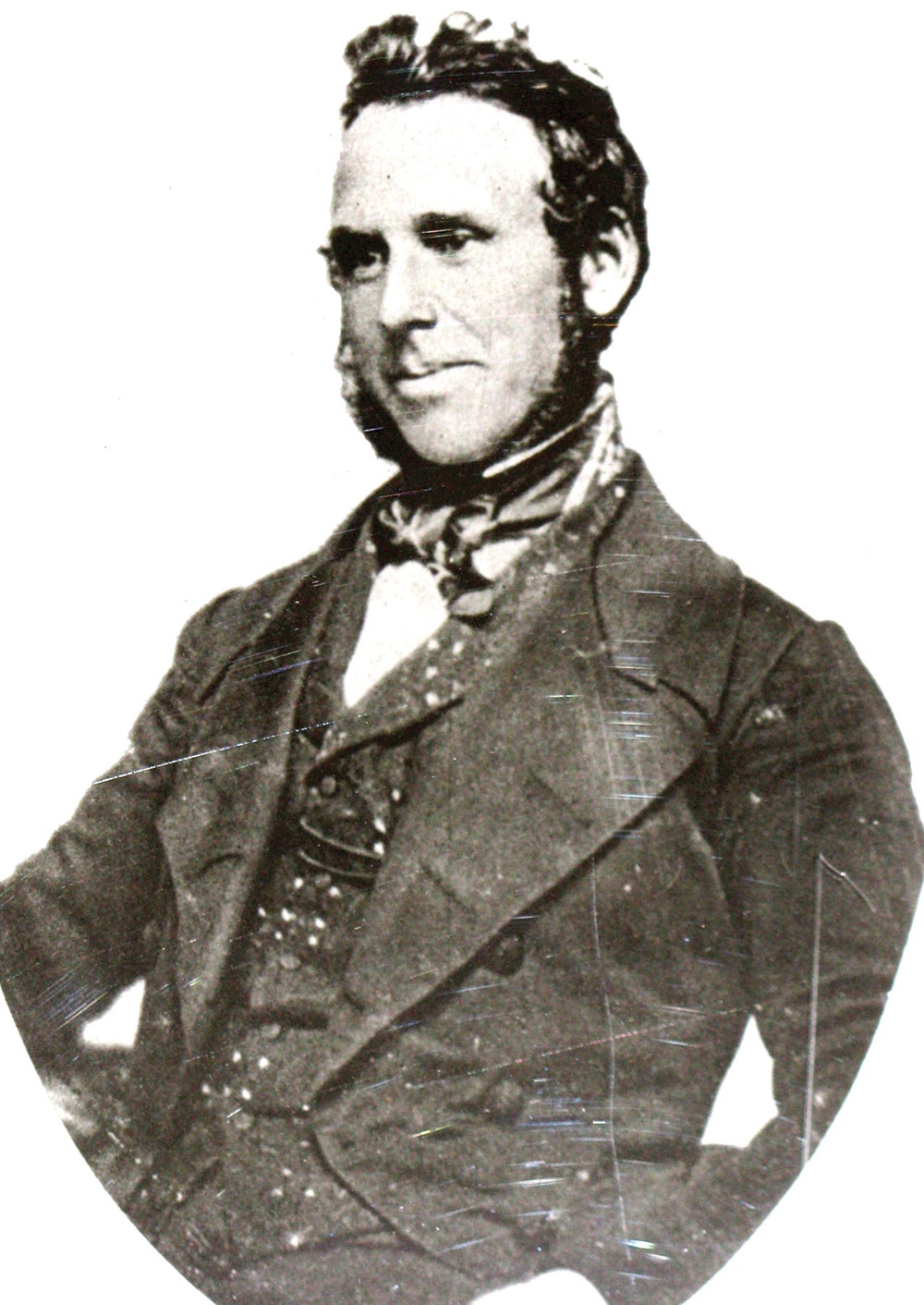

Another Centerville native, Josiah Richardson, married and moved to Shrewsbury after leaving command of the ship Chatham, which carried cotton from U.S. southern ports to Liverpool, England and Le Havre, France. He became a deacon and spent time planting fruit trees, but the siren song of the sea beckoned him again.

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

Richardson gained notoriety when Donald McKay, the architect/inventor of a new design of clipper ships that could travel long distances at high speeds, chose him to sail his new ship, Stag Hound. In 1851, The Boston Atlas newspaper described Stag Hound as “a new idea in naval architecture” and its master, Richardson, “as a gentleman of sterling worth as a man, and a sailor of long-tried experience.” While captaining another state-of-the-art McKay vessel, the Staffordshire, Richardson and 169 others died when the ship sunk after hitting rocks off Nova Scotia’s Sable Island on December 30, 1853.

The life of old Cape Cod is often told in its churchyard cemeteries. Gravestone inscriptions at the cemetery on Main Street and Church Hill Road tell of lives lost at sea, of deaths of infants and young children, and mothers dying in childbirth.

Photo courtesy of Centerville Historical Museum

The gravesite of brothers, Ebenezer and James Scudder, is a harsh reminder of the perils of the sea. Caroline, a sloop commanded by young captain James Scudder, capsized off Barnstable’s Sampson’s Island in February of 1829. James was 19 at the time—Ebenezer, just 13. Ebenezer perished from the cold, while James died of exhaustion a few hours later.

Much has changed in the village over the years. The salt works and many of the cranberry bogs are gone, as is the shipyard that was once on the Centerville River off Main Street. James and Samuel Crosby and Jonathan Kelley built 34 vessels of light tonnage here between 1824 and 1860, many of them specifically for Centerville captains.

The Centreville Wharf Company, built in 1852, was located on a strip of what is now Craigville beach. Vessels of up to 200 tons were built there, but the tide was changing both on shipping and the coastal trade. Stages and trains were transporting people and goods over land. These modes of transportation were also responsible for a new industry on Cape Cod: tourism. In May of 1879, the wharf sold at public auction: the building brought $73, the wharf property, $8.

A walk down Main Street today may elicit a sentimental longing for the past as one strolls by the old school building built in 1717, the 1856 Country Store, the South Congregational Church—and a collection of stately residences that Centerville’s ship captains once called home.