Manry on a Mission

Cape Cod Life / Annual Life 2015 / Art & Entertainment, History, People & Businesses

Writer: Matthew J. Gill

Manry on a Mission

Cape Cod Life / Annual Life 2015 / Art & Entertainment, History, People & Businesses

Writer: Matthew J. Gill

Remembering one sailor’s epic journey from Falmouth, MA to Falmouth, UK

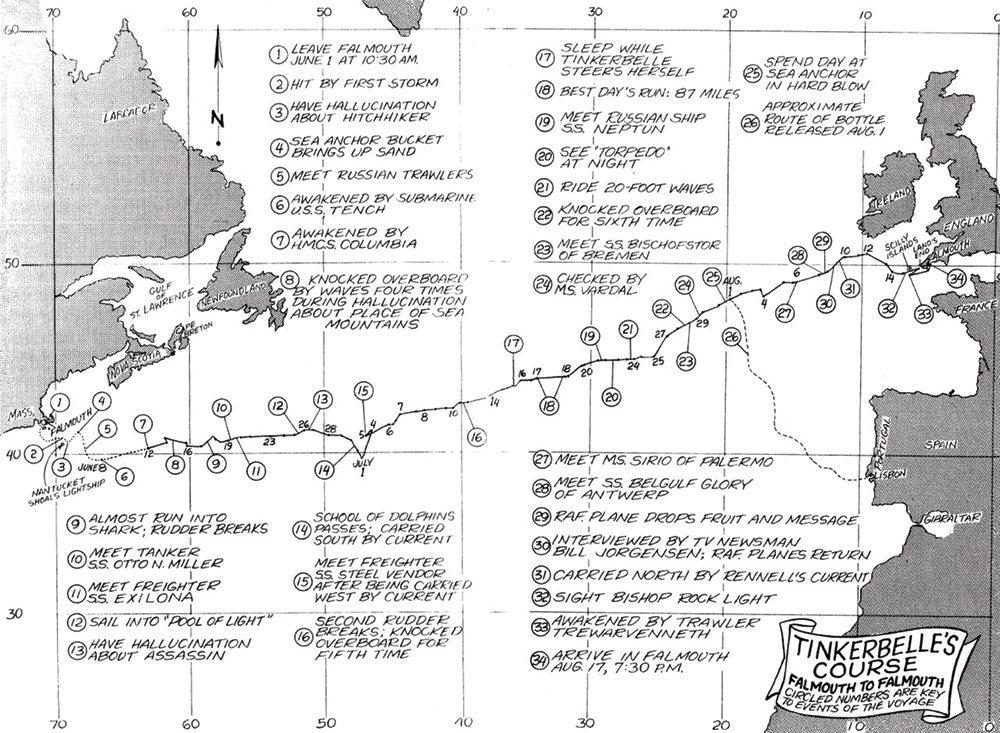

When Robert Manry arrived on Cape Cod in the spring of 1965, his visit began like that of countless other tourists drawn to the region. On May 25, he and his wife, Virginia, and brother-in-law, John, enjoyed a breezy breakfast in Woods Hole, did some antiquing in Chatham, and took a drive to Provincetown. In the following days, Manry brought his boat, Tinkerbelle, to Falmouth’s Inner Harbor–launching at Litzkow Marina–and prepared the boat for an upcoming sail.

When the marina’s owner, Bill Litzkow noticed the trio loading the 13-1/2 foot sailboat with an extraordinary amount of supplies, something, to him, seemed fishy. Lipskow allegedly then asked: “What is he planning to do, sail across the Atlantic?”

Painted by: Hannah Schoonmaker

Bingo. On June 1, 1965, Manry, a newspaper copyeditor from Willowick, Ohio and an experienced sailor, set off from Falmouth, commencing an epic, 2-1/2 month solo adventure that would bring him face to face with myriad dangers on the high seas—from sharks and storms to submarines—and eventually, 78 days later, to Falmouth, England.

Photo Courtesy of: Steve Wystrach

“Sailing was a central part of his life,” says Steve Wystrach, a filmmaker from Los Angeles who is currently putting the final edits on a documentary about Manry. “This was a dream he had had since high school. Unlike a lot of people, he kept that dream alive as he grew up, and when he had an opportunity to do it, he took off. He made it happen.” Like this article, Wystrach’s film is scheduled for a 2015 release to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Manry’s journey.

On the first day of the trip, Manry sailed out of Falmouth Harbor, around Martha’s Vineyard, and set a course eastward. Though a daunting endeavor, this sailor was prepared. Manry, who had grown up in India as the son of a missionary, had purchased the diminutive Tinkerbelle in the late 1950s, repaired it, built a cabin and deck for it, and readied it for many nautical miles to come.

Photo Courtesy of: Steve Wystrach

His supplies on board were thought out and organized, and included 27 gallons of water, a sextant, a sea anchor, and a hand-crank radio with which he could send out an emergency signal if the need arose. For sustenance, he had cans of tuna, vegetables, fruit, and more. He had divided his entire food supply into individual days’ rations, subdividing that further into individual meals. When he reached the journey’s halfway point, he celebrated with plum pudding.

Photo Courtesy of: Steve Wystrach

Though he would experience storms on the open ocean, Manry was less concerned about the weather than he was about another danger close to shore. “His greatest fear,” Wystrach says, “was crossing the shipping lanes and being run down by a ship.” Therefore, when he left the Cape, Manry kept himself awake for three days and two nights, using prescription medication to help stave off sleep. Near the end of that tiring stretch, he experienced the first of several hallucinations that would mark the journey.

One morning, a week after departing, Manry was awoken by “a bloodcurdling sound,” Wystrach says; it was a horn blast from the U.S.S. Tench, an American submarine. Manry had heard voices, but coming in and out of sleep, he shrugged off the sounds of the men talking on the sub’s deck; when the sub blew its horn, though, that got his attention.

En route, he saw sharks and dolphins and came across some 60 ships, including Russian trawlers, a Canadian destroyer taking part in a NATO anti-submarine exercise, and on July 5, the freighter, S.S. Steel Vendor—which stopped, chatted with him, and took his mail for posting.

The ocean itself was not always welcoming. Manry once road out 20-foot waves, and on a few occasions he was carried off course by strong currents. His rudder even broke—twice. He was thrown overboard a total of six times, though he was able to climb back aboard relatively easily as he had a lifeline tied to him for much of the trip.

Photo Courtesy of: Steve Wystrach

Other than these situations, bouts of loneliness, and the fact that the trip took longer than he had estimated, Manry generally enjoyed the adventure. “For the most part,” Wystrach says, “he felt it was very pleasant sailing.”

Manry was 47 when his journey began, and on a requested leave of absence from his position as a nighttime copyeditor for The Plain Dealer, a morning daily in Cleveland. What, then, was his connection to Cape Cod, or to Falmouth? “He was a newspaperman who came up with headlines,” Wystrach says, adding that Manry likely viewed “Falmouth to Falmouth” as great material for potential headlines.

From all accounts, Manry wanted to keep plans of his trip—or at least the more dangerous parts—secret before he set off. He had his family’s blessing, but colleagues and friends knew little about what he was planning. However, on May 31—the day before his departure—he wrote to his boss and colleagues, providing the true details of his “absence.” Naturally, his letters reached their recipients after the journey had begun.

Wystrach says news coverage of the story became, in fact, an important sub-story of its own. With Manry’s letter and confirmation from Virginia, The Plain Dealer published a small announcement of the adventure afoot. Then, as ships coming across him on the water began radioing in his position at points further and further east, interest in the story began to grow. Many copywriters in the U.S., England, and elsewhere began to root for Manry, Wystrach says, “as one of their own”; he was someone from the gray world of newspapers who was out participating in a real, colorful adventure. “They kind of pushed the story.”

Staff at The Plain Dealer furthered the story when they decided to bring Manry’s family to England so a festive reunion would await his arrival—and so the paper could land an interview with its star employee.

Learning of Manry’s exploits, WEWS Channel 5, a television station in Cleveland’s competitive media market, simultaneously flew a reporting team to England —in secret—with the goal of locating Manry on the water, nearing his journey’s end. With a similar idea, reporters from The Plain Dealer caught a ride aboard a Royal Air Force plane in an attempt to pinpoint Manry’s whereabouts. When they finally spied Tinkerbelle, the newspaper team peering down from above, watched, unknowingly, as Channel 5’s Bill Jorgensen—having arrived first, and by boat—conducted the first interview. “They’re looking down watching themselves be scooped,” Wystrach says.

Though he left the Cape in quiet anonymity, Manry arrived in England 78 days later to a hero’s welcome; a flotilla of boats sailed out to greet him, and the mayor was on hand at the dock. “Huge excitement had built up in Falmouth (U.K.),” Wystrach says. “They say there were 20,000 people that came out to meet him.” Manry would also be feted with a parade back home in Cleveland.

Photo Courtesy of: Steve Wystrach

“It was the fulfillment of a dream,” Wystrach says of Manry’s journey. “He set out to do something and was able to hold onto that dream for many years, and fulfill it.” In lectures he would later give, Manry offered an inspirational message, often commenting that with dedication and preparation anyone can make their dreams come true.

Despite the accolades and excitement, the adventure did have its drawbacks. “It wasn’t all positive,” Wystrach says. “For the kids, it’s a bit of a bittersweet memory; it was exciting to go to England, but afterwards, they started getting teased, and the family got nasty crank phone calls.”

In 1969, just four years after the sail, Virginia died in a car accident; in 1971, Manry died at 52 following a heart attack. The couple’s children, Douglas and Robin, were left at a young age without both of their parents. In 2005, John Heaton, a reporter for The Plain Dealer, wrote a reflective article, titled “The Cost of a Dream.” One of his interviewees was Douglas, who said at one point in his life he was homeless and had slept at least one night in the park in Willowick that was named after his father.

Wystrach, who has worked for years as an editor of television commercials, first learned of Manry growing up in Connecticut. “When I was a kid, like a lot of boys, I became interested in the idea of the adventure of sailing,” he says. Though his family did not own a boat, Wystrach learned what he could from books, reading descriptions of many sailing adventures. He recalls seeing an article that LIFE magazine published about Manry’s journey in September of 1965.

Years later, Wystrach learned how to sail, and found himself reading of singlehanded sails and trans-oceanic adventures. This led him to Manry’s book, Tinkerbelle. One chapter, with a detailed list of the gear Manry had on board, piqued Wystrach’s interest. The list included a 16 mm movie camera and several reels of film. “Immediately I was wondering,” Wystrach recalls, “what happened to the film?”

Wystrach reached out to Manry’s family, eventually speaking with his brother, who had the movies in his garage—and was preparing to throw them out. Over the years, Wystrach acquired more footage and news clippings—and has been working on his film, on and off, since then.

When Manry crossed the Atlantic 50 years ago this summer, his Tinkerbelle was the smallest boat ever to complete the crossing, headed west to east. Today, Wystrach plans to have his film, Manry at Sea, in the can by April. He’s also planning to host a screening in Cleveland on or before June 1—and another, across the pond, about 78 days later. Learn more about the film at robertmanryproject.com.