Grist for the Mill

Cape Cod Life / April 2020 / History

Writer: Chris White

Grist for the Mill

Cape Cod Life / April 2020 / History

Writer: Chris White

Every spring, for thousands of years, the sites of the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History and the Stony Brook Grist Mill & Museum have hosted a collision of natural forces. The geological genesis for this convergence arises from the close of the last Ice Age when the great melting of the Laurentide Ice Sheet created the peninsular moraine that is Cape Cod. Buried chunks of ice would later melt to form the dozens of ponds known as kettle holes. In Brewster, the interconnected Walkers Pond and Upper and Lower Mill Ponds are three such kettle holes. Water overflows from them down Stony Brook, racing north toward Cape Cod Bay, where salt water floods in on the tide to mix with the river and to host a wide range of wildlife throughout the marshes near Wings Island. In early-to-mid April, schools of fish from a species of herring called alewife race up Stony Brook to spawn in the fresh water ponds above the mill site. These “herrin’,” as they’re known locally, slither through shallows and battle rapids on their way up Paine’s Creek and Stony Brook. At the upper reaches of the brook, they climb in queues and orderly regiments up the concrete and natural ladder rungs of the herring run; they fall back, attack again, and rage against exhaustion, and against the rushing water and rocks. Their life struggle is unsubtle, and they fail to conceal their vulnerability as they attract legions of predatory birds, squadrons of seagulls all howling for herrin’.

That the alewife have for millennia run into Cape Cod Bay from mysterious, unknown locations in the Atlantic, up the run, and into the kettle holes is extraordinary; that their spawning waters and access have remained clean and open through the industrial and post-industrial ages is both nearly miraculous and due in large part to the vision of one naturalist and conservationist, and to the people of Brewster who shared his passion for the preservation of this watershed, a relatively small area that supports such a vast array of life. John Hay, a journalist and naturalist, moved to Brewster with his wife Kristi in 1946 after having written for the military publication “Yank” during WWII. They fell in love with the town, especially with its access to nature and wildlife, and they would raise their three children in the house that they built here. In 1954, along with seven other townsfolk, Hay founded what is today called the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History, (CCMNH). According to Bob Dwyer, the museum’s current president and executive director, Hay wanted to create something for local children. “Back in the 1950’s on the Cape, there wasn’t much for kids,” says Dwyer. “John Hay started the Children’s Junior Nature Museum to get them involved, to get them out into the natural habitat.”

The museum started out on the second floor of the old town hall, but it purchased a piece of land on Route 6A, a ways downriver from the herring run and the Stony Brook Grist Mill. Here, it set up a tent as a base of operations during the summers of 1961 and 1962. Over the following years, Dwyer recalls, the museum began building more permanent structures, and in 1968, the current building was erected. The Town of Brewster and the Brewster Conservation Trust have since acquired land along the brook, surrounding the 80 acres owned by the museum, so that a continuous area from Lower Mill Pond all the way to Cape Cod Bay is protected. Dwyer says, “It’s a microcosm of Cape Cod with salt, brackish, and fresh water through marshes and into upland forest.” Throughout the 50’s and 60’s, the museum continued to offer programs for children on site, and its staff visited schools in outreach programs. Dwyer says, “Hay wanted the museum to be a part of the habitat. If you came to the exhibits in the building first, the guided field tour would reinforce what you’d learned in the museum. But visitors could do this the other way, and the museum would reemphasize what they had discovered outside.” Hay served as president of the museum for 25 continuous years while simultaneously writing books about nature. In his forty-year career, he would publish 18 books, and grow into one of the most influential writers within the genre. Renowned essayist Annie Dillard wrote of Hay’s 1970 book, “In Defense of Nature”, that “John Hay is one of the world’s handful of very great nature writers; I love his books with all my heart.”

One of Hay’s recurring themes is the interconnectedness of life; the location of the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History on Stony Brook could not be more ideal with regard to underlining this concept. Hay, who passed away in 2011 at the age of 95, looked for the ways that living things are similar, and he recognized that even a fish could share qualities with humans. In his critically acclaimed 1965 book, “The Run”, Hay documents the annual return of alewife from the Atlantic to the kettle holes, and he devotes many pages to developing connections. Dwyer says, “He identified with the alewives’ struggles and with their danger.” Midway through an early chapter entitled “The Nature of an Alewife,” Hay ruminates on the fish’s eyes. He writes:

Its black, round shining eyes are very prominent in proportion to its small head and small mouth. They are large black discs like certain water-worn rocks, or they are great bubbles coming up from a dark depth. I fancied, seeing a tiny image of myself in the alewife’s eye, that I was reflected in a deep, impenetrable well.

Having established this poetic bond with the fish, Hay concludes the chapter more literally, asking:

Were there more connections between us that needed explanation? How much fright, how much nerve-threaded darkness, how much throbbing electric quickness might not be receiving me in the distance of that fixed eye? Perhaps we strangers all meet somewhere in each other’s sight.

Stony Brook and the herring run in Brewster serve not only as the conduit for the alewife, but as the connecting thread between the natural history museum and the Stony Brook Grist Mill and Museum. Yet another connection between humans and the natural world is both the herring run and the mill have served the food needs of the community of Brewster for hundreds of years. Even before the man-made concrete steps of the herring run were put in place, the alewife made their way up the brook, and the Wampanoag people caught them in the spring for eating and to use as fertilizer. Early English settlers learned from the Native Americans, and the effectiveness of the fish in growing corn is well documented. It’s somewhat poetic that the same brook that draws the alewife home year after year, century after century, turns the mill wheel that grinds the corn from those fish-fed fields. It’s surely appropriate that the current director of the Stony Brook Grist Mill and Museum, Doug Erickson, is both the miller and one of two herring wardens for the Town of Brewster.

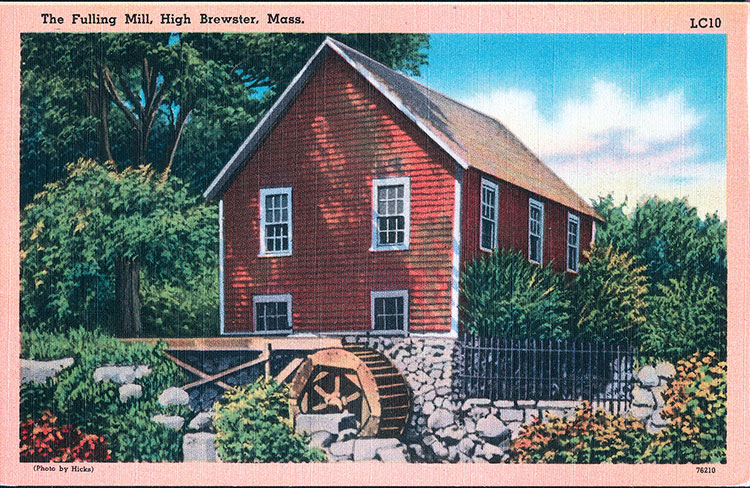

Throughout most of the years since Thomas Prence purchased the land in 1661 from the Wampanoags, water-powered mills have operated on or around the site of the current structure. To the early colonists, says Doug Erickson, “Corn was the staff of life. Cornmeal doesn’t keep very well, but dried corn does. People would eat cornmeal three times a day, and they would bring their corn to the mill as necessary.” For many years, the discarded cobs would be burned to smoke the alewife. The mill evolved over the years and took different forms. In 1665, it was a fulling mill. “Settlers would bring their preshrunk woolens there to be cleaned, to remove lanolin, and they’d hang them out on tenter hooks,” explains Erickson. In the 19th century, mills for weaving, woolens, paper, and a tannery all took root in the area. A few of the mills burned, and in 1871, Erickson says, “A roaring fire burned both the gristmill and tannery to the ground. It started because the miller was smoking herring and had gone into town.”

The area around Stony Brook eventually developed into a factory village, one of the first industrial sites in New England. Among other things, the factories produced ice cream, but eventually industry moved out. Private owners held the property through the 1930’s, but in 1940, the town voted to buy the land and mill sites. “The town raised $1,000 and donations from local citizens raised $1,200 for the purchase,” says Erickson. They rebuilt the water wheel and converted the building’s second floor into a museum. “People cleaned out their attics and basements to help out,” Erickson explains.

Today, the Stony Brook Grist Mill and Museum, the Herring Run, and the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History serve the community and its visitors in keeping with their individual and connected histories. Though the stocks of alewife have been in decline due to the combination of climate change and overfishing, hundreds of thousands of fish still fight their way upstream every spring, wriggling through a gauntlet of seabirds, through the Museum of Natural History’s property, up the ladder, and past the mill to the ponds above. Among local herring runs, Brewster’s is well worth a visit. On the first Saturday in May, as part of the Brewster in Bloom festival, the Stony Brook Grist Mill will begin its seasonal routine of grinding corn. Erickson says, “We usually grind and sell about a ton of corn each year.” Even if you’re unable to see the herring, the fresh ground cornmeal will be available on Saturdays throughout the summer.

Of course, the interconnectedness of nature from Cape Cod Bay up to the mill is accessible to everyone year round. John Hay would surely take pride in knowing that his vision persists, and visitors to Brewster are most welcome to the gifts of his legacy.

For more information, visit the Mill online here or make sure to stop by in person at 380 Stony Brook Road, Brewster!