The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: An introduction to our series

Editor’s note: Our April 2016 issue reintroduced The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands series to our readers after a successful run in 2015. Click here to see all of the articles.

“Rather suddenly, about 12,000 years ago . . .

“Rather suddenly, about 12,000 years ago, a rapid warming of the world climate set in and the ice sheets of North America and Europe began to waste away.” Such begins a paragraph in writer Arthur N. Strahler’s 1966 book, A Geologist’s View of Cape Cod, where the author describes the melting and retreat some 12 millennia ago of ice sheets that covered a good portion of the Northern Hemisphere, including New England—and our beloved Cape and Islands.

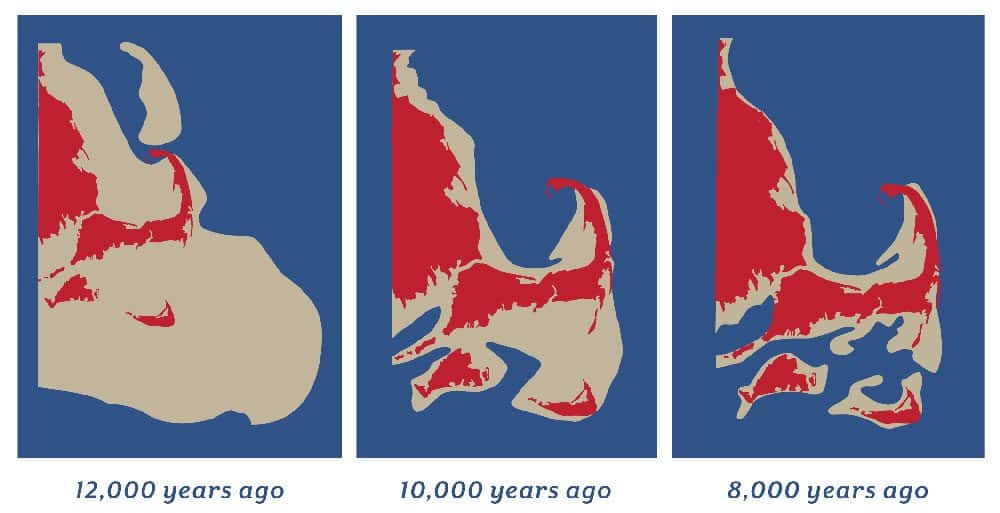

Graphics adapted from artwork created by Robert Oldale that is displayed at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History in Brewster

If you’re interested in the ever-changing shape of Cape Cod and the Islands—and how these areas were formed in the first place—we think you’ll enjoy our “Shape of the Cape” series. We rolled out the series in 2015, covering six topics ranging from Town Neck Beach in Sandwich to the dramatic “breaks” at popular barrier beaches in Chatham and Chappaquiddick. We had so much fun we decided to continue the series in 2016, and we have six articles in the works. To begin, check out writer Chris Setterlund’s coverage of the dramatic changes Mashpee’s Popponesset Beach Spit has undergone in recent decades.

Also, to get you in just the right geologic “mood,” we stopped in at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History in Brewster recently to photograph the panels that are displayed on these two pages. Created by Robert Oldale of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, the panels—which our creative director Jennifer Dow adapted into the graphics you see here—tell the visual story of what this region looked like 12,000 years ago, 10,000 years ago and 8,000 years ago. The final panel (opposite page) offers quite a forecast: 2,000 years from now a lot of the places we know and love will be all wet.

Returning to Strahler’s description from earlier: “Now the ice of the great continental ice sheets had been returned to the oceans in liquid form, causing the sea level to rise until a considerable part of the material deposited by the ice sheets was submerged and the shoreline had come to rest against the glacial deposits. The Atlantic Ocean thus entered Cape Cod Bay, Nantucket Sound, and Long Island Sound. The rising waters isolated Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Island . . .”