The Tides of Talent

Cape Cod Life / August 2023 / History

Writer: Michael Muroff

The Tides of Talent

Cape Cod Life / August 2023 / History

Writer: Michael Muroff

“[It was] a great summer, we swam from the wharf as well as rehearsed there, we could lie on the beach and talk about plays—everyone writing or acting or producing. Life was all of a piece, work not separated from play.”

– Susan Glaspell, writer and founder of the Provincetown Players

The turn of the 20th century saw a wave of artists and other creative types flood the Outer Cape for inspiration and community.

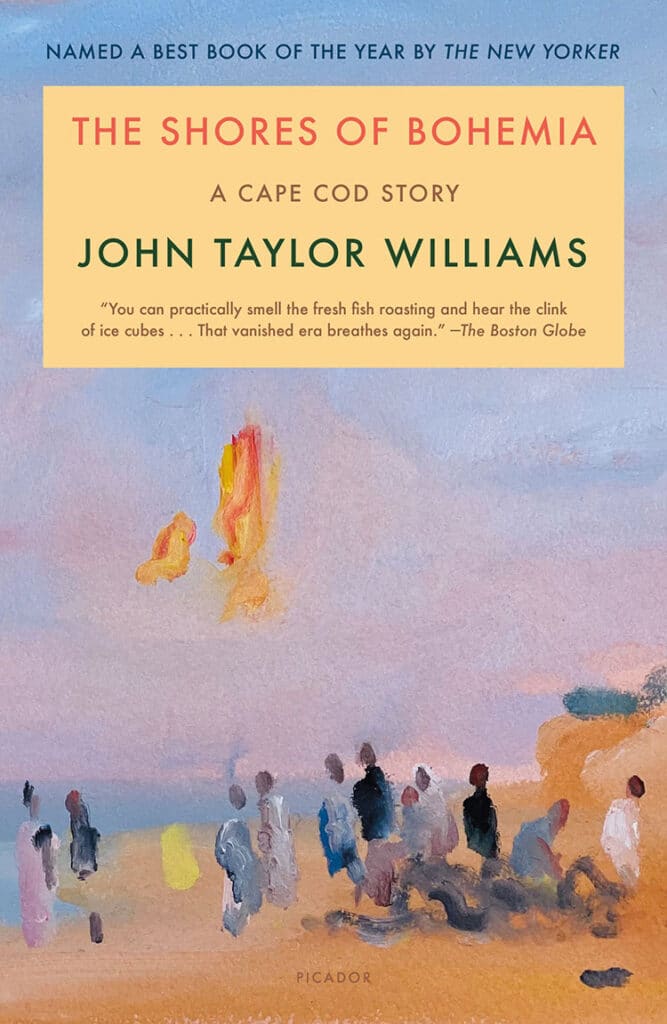

Susan Glaspell was one of many artists who sought the uniquely bohemian “work not separated from play” lifestyle found here on the golden shores of Cape Cod during the first half of the 20th century. Free from the restraints of Victorian-era life, inspired by all that has always inspired Cape artists, Glaspell worked and lived alongside many Black, female, Jewish, middle- and upper-class, openly gay and lesbian artists and activists who found a community of artists that individually and collectively helped shape the cultural and creative landscape in the country. The American bohemian movement, with deep roots in 19th century European cultural movements, was infused with the ideals of labor reform, the suffragists’ efforts and socialist leanings. The thinking of the time influenced art, architecture, music and literature. In his book The Shores of Bohemia: A Cape Cod Story, 1910-1960, John Taylor Williams skillfully weaves together the individual stories of 76 journalists, painters, printmakers, architects and playwrights who were a part of the bohemian movement in Provincetown—people like Pulitzer Prize winning playwright Susan Glaspell, Mary Heaton Vorse, a labor activist, journalist and novelist, and architect Jack Hall. Provincetown was a place where bohemian life could take hold and where residents could explore their sexual identity in conversation with the revolutionary developments they made in art, theatre, architecture, and writing. While some suggest the movement along the serene shores of Cape Cod may have lasted longer, Williams vividly paints a picture of Cape Cod bohemian life within the context of the historical developments of the time period from 1910-1960. Overall, Williams’ work masterfully captures the artistic and creative energy that flowed through the veins of Cape Cod and uniquely places this often-overlooked part of history into a much wider context.

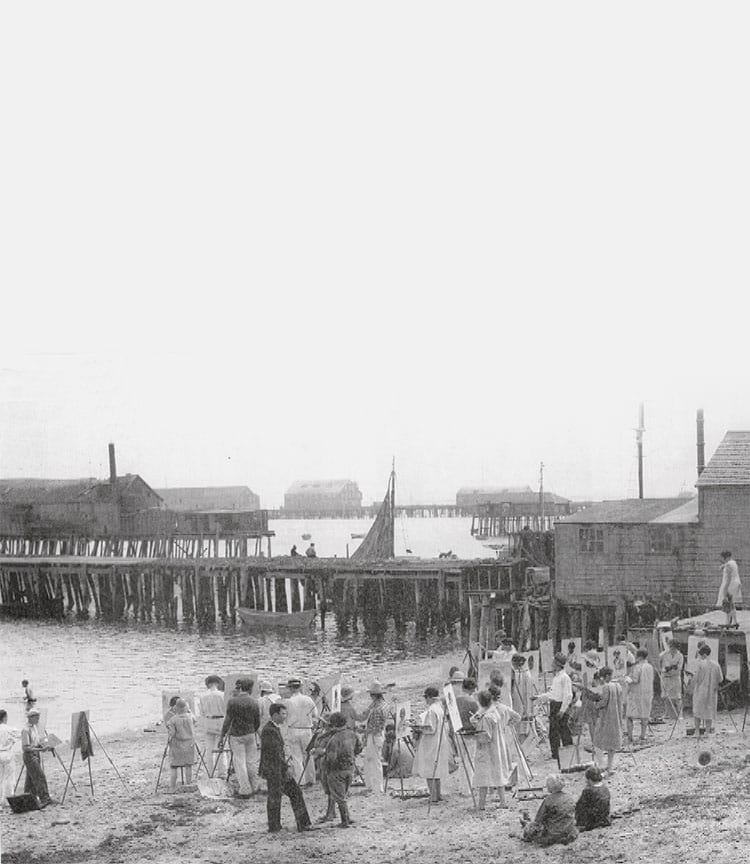

Vorse, along with artist Charles Hawthorne, was among those who lured friends and fellow artists away from Greenwich Village in New York, often dubbed the hub of the bohemian movement, to the sandy shores of Provincetown. Williams writes of Provincetown’s “swagger” and tolerance for alternative ideas, ideals and lifestyles that created the perfect climate for this bohemian movement to grow. Indeed, Vorse was not only known for leading her fellow bohemians to Provincetown and her skillful prose, but also for her help in organizing labor strikes and participating in the labor movements against then-Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. She wrote about and protested against the atrocities of the First World War.

In the early 1900s, Provincetown was littered with affordable houses along the East End, allowing these starving artists to come and move and set up shop. Lucy L’Engle, Hutchins Hapgood, and Neith Boyce joined the swell of other artists and writers, joining Charles Hawthorne to create the first Provincetown Arts Association in 1914, with its first two juried shows appearing in that same year. Soon thereafter, run-down fishing shacks became prized artists’ studios where artists could enjoy quiet for their work during the day and parties, cocktail clubs, and bars during the evening.

Joining Glaspell in the creation of the Provincetown Players was Eugene O’Neill, then a twenty-seven-year-old hungry playwright and son of the famous New York actor, James O’Neill. With the Provincetown Players, O’Neill featured his prized work, to which he devoted much of his life. His plays were, simply put, novel and revolutionary. O’Neill was the first playwright to cast a Black actor at the Provincetown Players. O’Neill’s Beyond the Horizon, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1920. Cast parties were lively affairs, Williams writes, “When accused of being drunk, he [George Cram Cook a.k.a. “Jig” Cook, a cast member and Glaspell’s husband and Provincetown Players founder] roared, ‘It is for the good of the Provincetown Players. I am always ready to sacrifice myself to a cause.’” And sacrificed himself to the cause of Provincetown theatre he did—as wholeheartedly as O’Neill and Glaspell did themselves. “The Cape,” Williams writes, “provided O’Neill with inspiration and was the one place where he found moments of joy and fierce physical relief…” Countless artists found the same great solace and creative inspiration here.

This cast of Cape Cod characters included architect Jack Hall, a graduate of Princeton and radical activist. Tiny Worthington, a tall Englishwoman, was best known for her fishnet shawls, jackets, and handbags, which were inspired by the fishermen’s work on the piers and beaches, and sold in high-end stores of Manhattan to people such as the Duchess of Kent. Tiny was also famous for having lovers of both sexes, more acceptable in Provincetown’s open-minded culture. Jack Phillips offered a center for the bohemian life when his uncle left him his hunting camp in Truro to Jack. The site consequently, became the unofficial capital of Cape bohemian social life. Williams writes, “on the pounding Atlantic, [Phillips’ land] seemed indeed like Eden to the New Yorkers who were lured there by Phillips’ social and personal magnetism.” Williams describes how many would line their cars along the road of Phillips’ house to sit and enjoy the sunset and stand over a warm fire pit while sipping on a drink. Phillips was indeed an essential piece of the fabric that made up the Cape’s bohemian life.

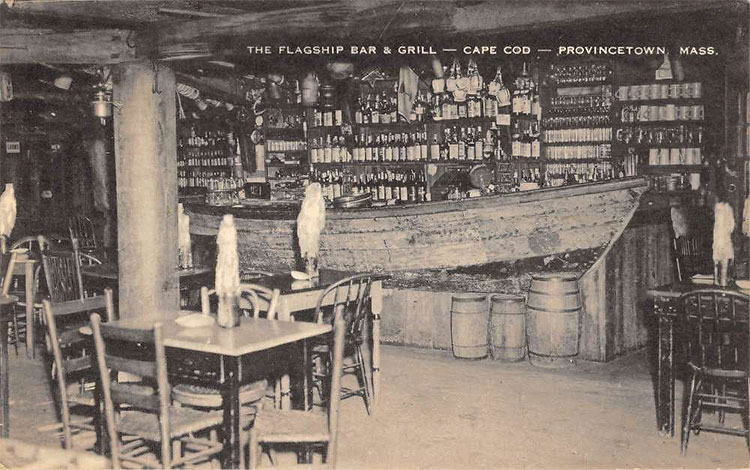

During the 1930s and the times of prohibition, depression, and war, artists gathered around some of their favorite watering holes, of which there were many. The Flagship, as it was known, was perhaps the most prominent. It was famous for its “Zombie” cocktails, its live music and rowdy clientele. Williams writes, “some bohemians drank for both social and professional reasons. Most writers and painters revered alcohol as a muse without whom they were often at a loss for inspiration.”

Also active along the shores of the Cape were closeted and openly gay and lesbian men and women looking for the social freedom to explore their sexuality. While much of the country was deeply intolerant of homosexuality, Provincetown became a bastion of gay life before it was widely accepted. Tennessee Williams, the famous 20th century playwright, became openly homosexual thanks to the beaches of Provincetown. He and Harvard poet, Frank O’Hara, would often frequent the nude beaches and talk extensively about creative life. Many bohemians, however, still remained closeted for most or for the entirety of their lives because of their strict Victorian upbringing or for fear of being called out. For whatever the reason, many bohemians elected not to reveal this important part of their lives to the broader community.

Alongside writers, sculptors, painters and performers, the bohemian community included architects who contributed to revolutionary developments in modern architecture. Many of the changes and ideas in this kind of building design can be attributed to European immigrants who collaborated with people here to design some of the most surreal and abstract houses on the market. Jack Hall’s house was described by Peter McMahon as one that “evokes the most visceral, astonished response, even from veteran architects.” Indeed, Cape Cod became a sort of “Periclean Athens,” as Williams writes, where the arts and architecture, particularly modern Bauhaus architecture, flourished.

The legacy of these trailblazers, known as the bohemians, is still present in the fabric of Provincetown and much of Cape Cod today. Helen Addison, at Addison Art Gallery in Orleans, is working to keep the legacy alive in an ongoing series of exhibits and events titled “Beyond Bohemia.” With art exhibitions, book signings, panels, music, live model painting, and plein air gatherings. One of the paintings currently on display at the gallery by Paul Schulenburg, is the only known portrait of Mary Heaton Vorse, a beautiful image with Provincetown in the background. The painting ties past and present into a lasting presence.

Michael Muroff, a recent graduate of the College of the Holy Cross, is a freelance writer for Cape Cod Life Publications.