A Place to Call Home

Cape Cod Home / Winter 2016 / Home, Garden & Design, People & Businesses

Writer: Chris White / Photographer: Dan Cutrona

A Place to Call Home

Cape Cod Home / Winter 2016 / Home, Garden & Design, People & Businesses

Writer: Chris White / Photographer: Dan Cutrona

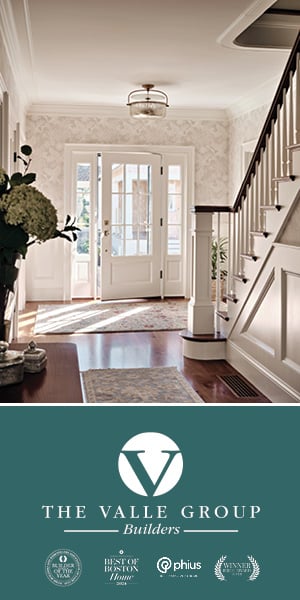

A renovated family house in Osterville now offers space for multiple generations

Photograph by Dan Cutrona

Each spring, David Herrlinger meets his neighbors to trim the 160 cedar trees that dapple the floodplain between their houses and Osterville’s North Bay. They gather with loppers and trimmers to prune the trees into balls of various shapes, like static planets ranging in size from Jupiter to Pluto, and perhaps an asteroid field. The annual ritual serves a few important purposes: it helps the neighbors maintain their views of the water by preventing the cedars from reverting back to natural states; it keeps the trees healthy and guards against erosion; and it bonds the men together throughout their hours of yard work. While Herrlinger’s cedars are nothing like a fence, his tradition of pruning shares much in common with the one described by Robert Frost in his famous poem “Mending Wall,” in which two neighbors rebuild the stone structure that divides their properties.

Just as Frost’s stone wall is an emblem of New England culture, the cedars represent an extended family: they grow in common ground with roots intertwined, yet each remains a distinct organism with its own branches and leaves. And if Frost’s poetry is iconic to the region as a whole, then the shared family home is quintessential to the fiber of Cape Cod, as ingrained in the sand as oyster shells. Which leads to the main reason for Herrlinger’s work each spring—the cedars, an archipelago of landscape that both protects the property and enhances its views, complete his family’s recently renovated home.

For every extended family that shares a house, the chief challenge is the same: how can everyone fit into one confined space, especially once the family expands beyond the nuclear with new generations of children? Many families separate as their living spaces fail to fulfill the needs of their various parties. The Herrlingers, however, dedicated their recent remodeling project to repurposing their house in such a way that each family member could feel perfectly at home.

The original owners handled their space dilemma in a different way: they had enjoyed the luxury of owning a neighboring house, which has since been moved farther across the street. Helen and David Herrlinger report that the parents inhabited the back property while the children and grandchildren stayed in the other. This seems to explain why the original kitchen lay just inside the front door. One can imagine a son or a daughter calling across the yard to a parent, asking, “How many cups of sugar do I need for these cookies?” With the two houses paired together as they were, form followed function, but once the separation occurred, the kitchen’s layout became rather odd, and in need of an update.

Photograph by Dan Cutrona

When Helen and David Herrlinger committed to the notion of leaving their permanent residence in Cincinnati and moving into their summer home in Osterville full time, they understood the need for a transformation of space that would include both an exterior expansion and an interior overhaul. They also wanted to transplant as much of their history and memories as possible, but the challenges were myriad. To accomplish these tasks, the Herrlingers enlisted the architectural firm of Brown Lindquist Fenuccio & Raber, of which Tom Swensson would serve as project manager, and they commissioned their son Cooper Herrlinger to design the interior. To the family’s delight, Cooper, a Boston-based interior designer, was able to, according to Helen, “fit everything” from Cincinnati into the smaller space of Osterville—while simultaneously managing to avoid any feelings of cramped-ness that had restricted the original home.

At the most basic level, the two houses could hardly have been less similar—one of vast English Tudor style with high ceilings and oversized rooms, totaling approximately 8,000 square feet; the other a 4,000-square-foot gambrel of 1950s New England design with much smaller spaces, including cubby-like bedrooms. “The two houses are like night and day,” says Cooper. “Cincinnati was quite formal, with a lot of darker colors.” For the new look of his family’s Osterville home, Cooper made a concerted effort to “try to make things less serious, with fresh, upbeat colors.”

Another part of the puzzle was how to work with the antique pieces, which the family wanted to keep because, as Cooper explains, “they tell a story.” In order to put everything together, some of the furniture required alterations. For instance, he shortened the legs of the secretary, which stands near the front door, so that it could fit more naturally in its new setting. Due to the smaller scale of the Osterville home, Cooper says one of his goals was to create a greater sense of comfort.

Swensson notes that the Herrlingers were already “very attached to the home as it was, but it didn’t meet their needs” any longer. With three grown sons living in Boston, they wanted to create a house that all could share, that each family unit would want to visit on a regular basis.

Photograph by Dan Cutrona

For the redesign, David and Helen moved their own bedroom downstairs and converted the upstairs into an area for their sons and grandchildren. Prior to the changes, they had felt cramped. Now the younger generations, as Helen points out, occupy the entire second floor. “They have their privacy,” she says, “and we never go upstairs anymore.” To create this new space, Swensson and builder Steven Bishopric extended each side of the home’s gambrel center portion. This expanded the overall floor plan by about 1,500 square feet, to roughly 6,500 in total. Swensson states that, “David was very concerned about the appearance from the water—he thinks of this as the front side of the house—so there were issues with balance and symmetry that we had to work out.” The building team also redid all of the exterior finishes including the shingles, and they added a new roof.

Many of the interior changes involved light and, as Cooper puts it, “crispness.” He reupholstered nearly 40 pieces of furniture in an effort to both preserve the original pieces and update them for their new seaside environment. What had been black leather wing chairs in the family’s Cincinnati library, for example, morphed into much brighter chairs clothed in pink and white linen. Helen notes that “the entire house is wallpapered,” which, Cooper adds, “makes it warm and welcoming.” The only piece that the designer kept in its original garb is the sofa in the living room, but he “freshened this up with new white pillows.”

Though the home was built in the early 1950s, Helen Herrlinger’s mother purchased the house in 1968 and had been its owner for more than 25 years. During that time, the family had made few changes. As is the case with many older Cape Cod homes, the cedars and pines had grown up around the property, which imparted a forested feel. In those days, David states, “you couldn’t even see the water.” In addition to the shrubs and trees growing in the floodplain between the back yard and North Bay, phragmite reeds also loomed as both a visual and physical barrier to the water. Then, in 1990, the family was able to fell 18 trees, and the state of Massachusetts changed its laws about phragmite, allowing for its removal, which, as David notes, “was a blessing.”

One of the key changes to the physical layout of the home has been the addition of a huge picture window in the living room. When one enters this space now, it’s impossible to avoid the view, which practically pours into the room—the yard stretching across to the floodplain and its manicured cedar trees, and, of course, the water. Just to the northeast, along the beach, the vista includes St. Mary’s Island, and directly across the bay one clearly sees the shoreline and mansions of Oyster Harbors. One’s gaze can travel into Cotuit Bay as well. As a result of these changes, the living room has become a space that the Herrlingers “use all the time,” according to Cooper. “In Cincinnati it was one of those big, unused spaces,” he says.

Photograph by Dan Cutrona

While the living room is Cooper’s favorite, he acknowledges that the most significant change to the Osterville home has been the kitchen, designed by Becky Brown of Classic Kitchens & Interiors. As previously noted, the original kitchen lay next to the front door, “back where people wouldn’t really want to spend time,” Cooper says. Still, before the transformation, the Herrlingers would gather in that space, despite its lack of a view. Swensson states that the new kitchen is set in a “modest addition” to the home. Yet, for many family members, this is the space that is most special. David notes that its dimensions are 14 by 22 feet with a bay window and claims that “most people spend the most time here.” A table set beside the window affords the same spectacular views as those from the living room, and the open counters allow the Herrlingers to “cook as a family,” as Cooper points out. “This is the change,” he adds, “that really updated the flow of the house.”

The Herrlingers’ summer home in Osterville always contained and created warm memories, but spaces were small and blocked off. For the renovation, Cooper says the family wanted an open floor plan instead of smaller separate rooms. “Everything flows now,” he says. A major element in this process was the way the various teams worked together, and, like the space itself, it was important for the overall synergy to flow. Swensson explains that the whole family contributed ideas. “The other two sons, Carey and Christopher, had input,” he says, “especially in the beginning and more again at the end, but Cooper worked as a go-between.” In the process, Swensson and the Herrlingers developed a strong friendship, and they continue to visit with each other.

David further emphasizes that the re-creation of the home has been a “democratic process.” After the family members had all agreed to the proposed exterior changes, they continued to share in the decisions so that each constituent’s needs were met. “We’d have family discussions, and sometimes you can have too many cooks, but in this case, everyone’s involvement helped the end product,” Cooper says. “Even though only our parents live here year round, ours is definitely a family house.”

Chris White is a freelance writer who teaches English at Tabor Academy in Marion.