The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: The Atlantic Shoreline

Cape Cod Life / 2018 Annual / History

Writer: Christopher Setterlund / Photographer: Josh Shortsleeve and Paul Rifkin

The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: The Atlantic Shoreline

Cape Cod Life / 2018 Annual / History

Writer: Christopher Setterlund / Photographer: Josh Shortsleeve and Paul Rifkin

Editor’s note: This is the 19th in a series of articles covering the region’s dramatically changing coastline. Click here to see all of the articles.

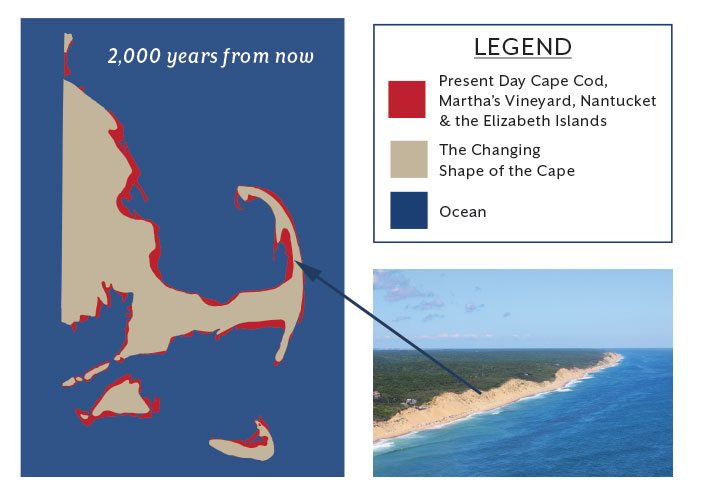

Pictured here, the portion of the Atlantic coast of Outer Cape Cod from Truro to Provincetown. Photo by Paul Rifkin

Beginning in April 2015 and spanning 18 articles since then, Cape Cod LIFE has showcased many localities on the Cape and Islands that have been affected by shoreline change. The “Shape of the Cape” series has shined a light on the situation of places such as Town Neck Beach in Sandwich, Lewis Bay, the Monomoy Islands, Great Point on Nantucket, and many more.

If Cape Cod is shaped like an arm, the portion known as the Lower and Outer Cape would extend from the elbow up to the hand. This includes the towns of Chatham, Orleans, Eastham, Wellfleet, Truro and Provincetown. It also includes the entire 43,600-acre Cape Cod National Seashore. The Outer Cape perhaps more than any other area on the peninsula has changed extensively over time.

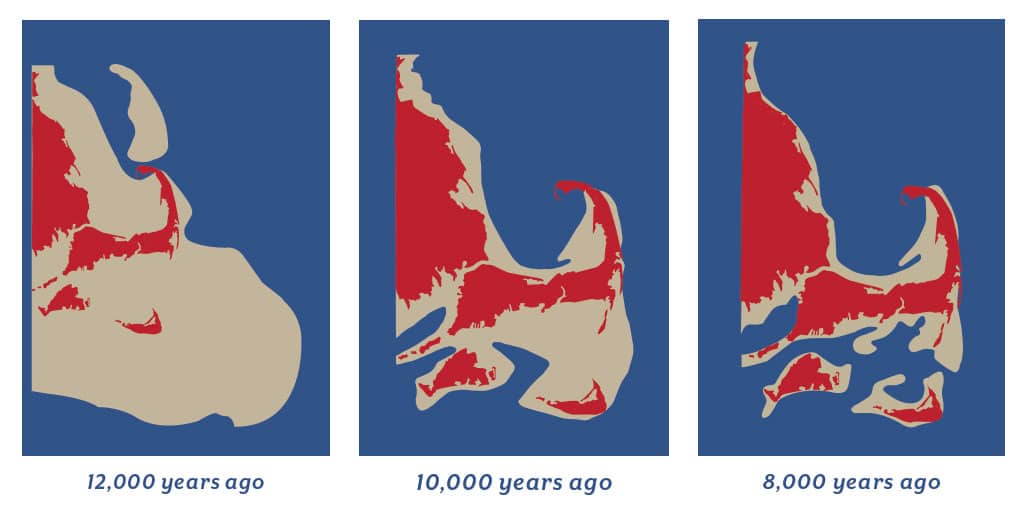

According to the 2015 “Guide to Coastal Landforms and Processes at the Cape Cod National Seashore, Massachusetts—A Primer” by the USGS, Cape Cod’s history goes back about 15,000 years when the continental ice sheet originating in Eastern Canada retreated and left behind deposits of sand, granite, gravel and silt. In the years following that retreat the sea level rose by about 400 feet, which submerged much of what the ice had left behind. By 10,000 years ago the sea level had risen to such a point that it was beginning to submerge previous land masses. This included Stellwagen Bank, an area stretching 19 miles north-northeast off the coast of Provincetown, and Georges Bank, an area 62 miles off the east coast of Cape Cod that is larger in area than the entire state of Massachusetts.

Left: Graphic adapted from artwork created by Robert Oldale that is displayed at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History in Brewster. Bottom right: Lecount Hollow and White Creast beaches, Wellfleet. Photo by Paul Rifkin

“Eleven thousand years ago Georges Bank was above water,” says Greg Berman, coastal processes specialist for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. “Back then it would have been possible to walk from the Cape to Georges Bank. With much more land visible, the Outer Cape was not getting hit with the large storms of today which come across the Atlantic, so erosion was much less.”

According to Berman, it was 6,000 years ago when the coastal erosion of Cape Cod began accelerating. The bluffs, which are retreating to this day, once extended as much as four miles farther east than they currently stand. Interestingly, although much of the eastern-facing coastline is retreating, there is an area which is actually growing. Due to wave conditions and sediment migration, much of what was lost from the eroding bluffs traveled north to create Provincetown and south to create Monomoy Island.

Dan Zoto, an archaeologist at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History, says that it was about 3,000 years ago when the sea level stabilized. He explains the importance of the stabilization: “Sea level stabilization allowed for the initial formation of barrier beaches,” he says, “and not long after came the beginnings of salt marshes in the estuaries and along tidal rivers. It is at this time, approximately 3,000 years ago, that we see intense use of these estuarine environments by Native peoples.” In other words, sea level stabilization allowed for the year-round habitation of Cape Cod.

Mark Adams, coastal geologist, geographer and cartographer at the Cape Cod National Seashore since 1991, expands on Greg Berman’s points. “Geologists have put together a picture of change going back to the glaciers about 22,000 years ago,” Adams says. “The erosion and accretion we see today has been going on for about 6,000 years, but the conditions began to change marginally in the industrial period over the last two centuries. We see the cliffs of the Outer Cape retreating at a rate of about 3 to 5 feet per year, so in my 20-year tenure that would be up to 100 feet of retreat.”

Today the east coast of Cape Cod is in a state of constant flux. In the town of Chatham it begins with the area once known as North Beach. Before 1987 there was a long barrier beach stretching down from Nauset Beach toward Monomoy Island. The rates of erosion along this barrier beach ranged from as high as 19 feet per year to 3 feet per year between 1938 and 1974. In January 1987 a powerful nor’easter caused the ocean to finally break through the barrier. The ocean poured through the hole into the Chatham shore and Pleasant Bay. This break created the popular Lighthouse Beach, located across the street from Chatham Lighthouse.

Graphics adapted from artwork created by Robert Oldale that is displayed at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History in Brewster.

Dr. Graham Giese, director of the Land and Sea Interaction Program at the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies, notes that breaches in this area are not exactly new. “Breaches happen and then close—there’s an overall pattern,” he says. The Chatham barrier beach has “been studied way back since the 1800s,” and at one point was the subject of a doctoral dissertation. It is part of a barrier beach system that undergoes cycles of roughly 150 years. “At certain points in history it is one continuous barrier beach, and every 150 years or so it goes back to that configuration.”

Berman says the break at the northern tip of North Beach Island, which allows water to enter Pleasant Bay, is increasing while the break adjacent to Lighthouse Beach is slowly diminishing. Although it is not to that point yet, Berman says there may possibly come a time in the near future where the Town of Chatham will have to decide whether to dredge the closing channel or let it seal and use the wider Pleasant Bay channel to the north.

Approximately eight and a half miles north of the Pleasant Bay channel is the Nauset Spit. The spit is a roughly two-mile-long section of the Nauset Barrier Beach, which, due to longshore currents and large storms, has gradually been stretching its way from Orleans up into Eastham.

One issue that has arisen with the spit is the fact that Orleans and Eastham have different Off Road Vehicle (ORV) laws. For many years beachgoers had been entering the growing spit in Orleans and simply continuing the drive north into Eastham, where driving on the beach has been prohibited south of Coast Guard Beach since 1978, leading to a dispute between the towns.

The entrance to the Nauset Inlet is approximately 280 feet wide. It separates the spit from the southern end of the Cape Cod National Seashore and Coast Guard Beach. This beach, routinely voted one of the best in the country, has seen its shore ravaged by erosion. During the Blizzard of ’78, the 146-car parking lot, which had been built in 1964, was destroyed, along with author Henry Beston’s dune shack, the “Outermost House.”

The A. Thomas Dill Beach Camp, now part of the Swift-Daley House Museum in Eastham, once stood among those same dunes as Beston’s shack. It was in fact the only shack to survive the Blizzard of ’78. Dill’s son Tommy, a resident of Eastham for all of his 86 years, remembers what Coast Guard Beach used to look like.

The Chatham Break and Monomoy Island. Photo by Paul Rifkin

When the family dune shack was built, “It was built on the back side of the sand dunes that stood as much as 50 feet tall,” Dill says. “It was on the marsh side of the dunes, not the ocean side. When I returned from Florida after the winter, mine was the only place still standing while eight or nine others were all washed away. I used it for another couple of years before I donated it to the Eastham Historical Society and it was moved before it fell into the ocean.”

Dill, who lives in a house overlooking the Nauset Inlet, says that when he first moved into the house in 1958, the dunes were so high that one could not even see the ocean.

“You wouldn’t even have recognized Coast Guard Beach then,” Dill says. “The whole place has changed.”

Greg Berman sheds light on why such changes take place on the east-facing Cape Cod shoreline. “The Atlantic shore is much more exposed,” Berman explains. “It does not have the protection of Cape Cod Bay and Nantucket Sound. Therefore much of the Atlantic coast is eroding at an approximate long-term rate of three feet per year where Cape Cod Bay and Nantucket Sound erode at a rate closer to one foot per year.”

Just above Coast Guard Beach is neighboring Nauset Light Beach; both are within the Cape Cod National Seashore. To cope with the constant barrage of the sea, in the fall of 2017 the park service removed the Nauset Light Beach restroom and changing building, septic tank, and stairway to the beach.

The decision to remove the stairway was a financial one, according to Karst Hoogeboom, chief of facilities and maintenance for the Cape Cod National Seashore. He explains that the stairway, a massive structure, had to be replaced an average of every three years, at a cost of around $130,000. The Seashore looked into alternatives and decided to replace the stairway with an engineered pathway just south of where the stairway once stood. The bathhouse will be temporarily replaced by trailers while the Seashore formulates plans for a new bathhouse closer to the road.

Berman says creation of the National Seashore minimized coastal damage. “Property damage doesn’t happen as much, since the area is mostly undeveloped,” he explains. “There is not as much of the man versus nature aspect on the ocean side of Eastham and Wellfleet due to it being National Seashore land, whereas the bay side is more heavily developed.”

In the Town of Truro, the dune system at Ballston Beach has been severely damaged due to overwashes. During a blizzard in February 2013, the storm surge at high tide broke through the dunes, pushing water from the ocean all the way back to the Upper Pamet River Valley more than 900 feet from the shore. In an attempt to repair the damage, which included further erosion of the dune and flooding in the beach’s parking lot, the Truro Department of Public Works trucked in 4,000 cubic yards of sand from Head of the Meadow, another beach in town. On January 27, 2015, Winter Storm Juno tore through the repaired dunes. The high tides, combined with strong winds, caused an overwash that once again flowed into the Upper Pamet River Valley, flooding the beach parking lot and pushing sand into the marsh. At 205 feet, this opening in the dune was even wider than that of 2013.

The parking lot of the Beachcomber in Wellfleet is perched atop an eroding cliff, and last year saw a sinkhole open up and swallow a car after heavy rain caused water to pool in the lower portion of the lot. Photo by Josh Shortsleeve

As residents of the area are likely aware, these incidents in 2013 and 2015 are not isolated. In 1978, and again in 1991 and 1992, overwashes were recorded at Ballston with seawater mixing with the fresh water marsh system and the beach parking lot being flooded.

Karst Hoogeboom notes the breach at Ballston “is happening more frequently now,” most recently in the early January 2018 storm.

As previously stated, some of the sediment from the beaches from Chatham to Truro is carried north and deposited along the shores of Provincetown. In particular, Race Point Beach, near the lighthouse, has one of the highest accretion rates on Cape Cod. According to the USGS, in 2013 the rate of accretion was approximately 2.3 meters per year.

Mark Adams explains the difficulty in tracking and predicting where the biggest changes will happen. “While we understand the long-term processes,” Adams says, “in the short term we see temporary ‘hot spots’ with sudden rapid erosion, likely driven by breaks in submerged sand bars near the shore.”

One such hot spot was at Cahoon Hollow Beach in Wellfleet. On August 18, 2017, heavy rains pelted the area and collapsed a section of the parking lot of the Beachcomber restaurant, leaving a 25- by 40-foot crater in its wake. A week later a new safe pathway was opened to allow beach access again. Though it may have looked like erosion, Greg Berman says it was something different.

“I was called to the site after the sinkhole opened,” he says. “It was not ocean-driven erosion, though. It was a heavy rain event where the water pooled in the parking lot causing the ground to give way. It was nothing that could have been predicted based on incoming storms and waves like common shoreline erosion.”

Adams says that in terms of solutions to the erosion issues, it is better to adapt than it is to try to stop it. “Soft coastal protection, which includes fences and planting, can help with minor erosion,” he explains, “but it only controls foot traffic and wind. Hard protections can have a temporary effect but have consequences downdrift by blocking the flow of sand.” This means that while structures such as breakwaters protect what is in the immediate vicinity, the areas located slightly farther away become sediment starved, essentially transferring the erosion to those areas.

Tommy Dill’s conclusion is simple yet profound. “You’re not going to stop the ocean,” he says. “It’s going to do what it wants to do. Every year things change.”