The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: Cape Poge and North Neck, Martha’s Vineyard

Editor’s note: This is the 15th in a series of articles covering the region’s dramatically changing coastline. Click here to see all of the articles.

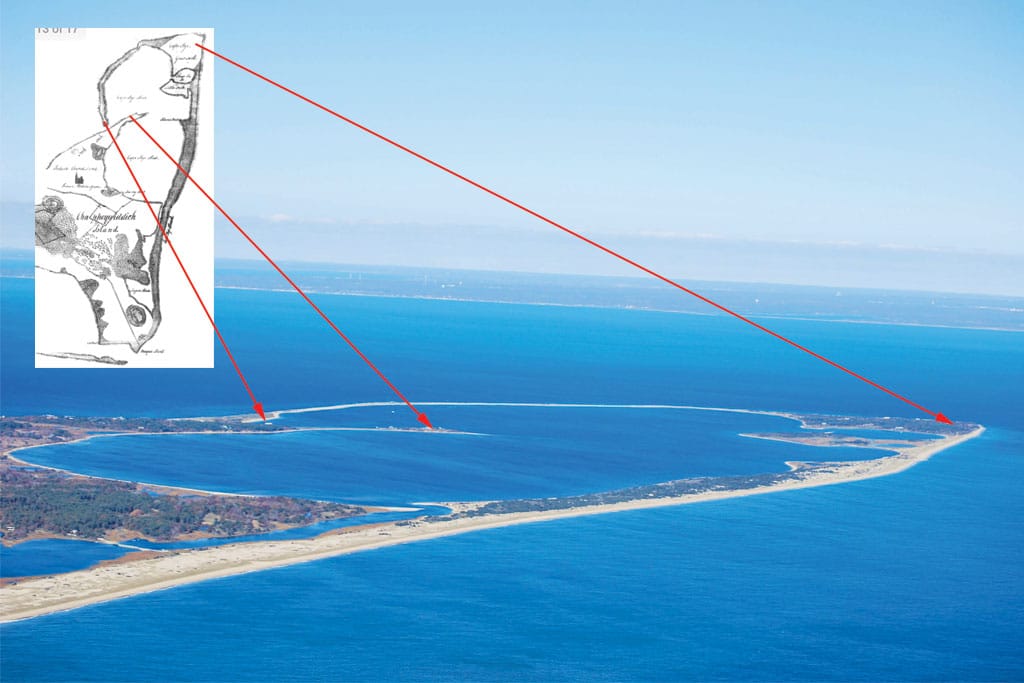

In this eastward-looking aerial photo of Chappaquiddick on Martha’s Vineyard, one can see Cape Poge Bay and the barrier beach known as “the elbow,” which winds around to protect it. In stark white, Cape Poge Lighthouse can be seen at the center of the image, and at bottom right, North Neck juts into the bay. Photo by Paul Rifkin

Visitors to the southeast of Martha’s Vineyard will find Chappaquiddick, a scenic swath of land that’s home to hundreds of acres of wildlife preserve, a few homes and a spectacular public garden. Chappaquiddick is also well known for sometimes being a peninsula, sometimes an island. Currently, “Chappy” is connected to the rest of the Vineyard by Norton Point Beach, which stretches from Katama Beach to Wasque Point.

On the north of Chappaquiddick, The Cape Poge Wildlife Refuge consists of 516 acres of marsh, dune, tidal ponds and barrier beach. It’s also home to the Cape Poge Lighthouse. First built on Cape Poge’s northeastern tip in 1801, the light has been rebuilt a few times and moved back from the shore on several other occasions, most recently in 1987. This last move brought the light 500 feet inland, but in the 30 years that have passed since then, that distance has been whittled down to 425 feet.

In addition to the lighthouse, Cape Poge also has nine residences, many of which were built as summer cottages but have since been winterized. Though these homes are not in any immediate danger, Chris Kennedy, the Martha’s Vineyard superintendent for The Trustees of Reservations, says erosion rates vary all over Cape Poge. “It depends on where you look,” Kennedy says. “The northeast tip has been undergoing constant changes for more than 200 years. Then, along the elbow, there has been almost nothing in terms of erosion.” Kennedy says that with an average erosion rate of nearly two feet per year over the past two centuries, the site of the lighthouse’s original 1801 foundation is likely 400 feet off shore today.

The elbow is a barrier beach that curls southwest from Cape Poge for about a mile and a half, almost all the way to North Neck, creating a protective barrier around almost all of Cape Poge Bay to the east. Boaters can enter the bay from Nantucket Sound, in the west, via Cape Poge Gut, a channel just north of North Neck.

A northwest-facing view of Chappaquiddick’s Cape Poge. Cape Cod can be seen in the background. Photo by Josh Shortsleeve. Inset: 1830 map of Chappaquiddick courtesy of Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Photo by Josh Shortsleeve

At its widest point, the elbow is 250 feet across, but according to Edgartown Harbormaster Charlie Blair, the southern tip has remained stable in recent years as a result of natural accretion and some beach re-nourishment where dredged sediment from the gut has been used to bolster the beach. Blair says the inside delta of the gut was last dredged in 2008, and town officials are considering additional dredging work in the area.

North Neck is another unique topographical feature. The peninsula extends some 2,000 feet into Cape Poge Bay, which is a popular spot for fishing and bird watching. Blair says the area around the neck has also been rather stable. “The current runs hard into the gut, and the sediment is pushed past the neck into the bay,” he says. “In looking at old maps of the area, North Neck looks the same as it did back in 1938.”

Though the neck, which does not face the open ocean, has remained mostly unchanged for at least several decades, the area just outside the gut has a different story to tell. “The bluff has been eroding my whole lifetime, and I’m nearly 70,” says Blair, referring to the coastal area southwest of the channel. “It has been peeling off, putting the houses at the top in serious danger.” Blair estimates that seven or eight homes, in addition to the historic Big Camp building near the Royal & Ancient Chappaquiddick Links golf course, are at risk from erosion. In recent years, property owners have taken some preventative measures, including planting vegetation on the bluff and installing stone bulkheads at its base.

During a 2011 storm, the elbow was breached about 200 yards to the south of a longtime summer camp known as the “windmill house,” where the beach measured just 75 feet across. A temporary channel developed—180 feet across and several feet deep. According to Kennedy, the breach filled in within a few weeks and no breaches have occurred since. This, Kennedy says, is most likely because the elbow is a “cobbled beach,” or one with a granite “spine” just under the surface, making it rather stable. “Often, breaches just happen,” Kennedy says. “It takes the right storm with prolonged winds from a specific quadrant to move the sand. However, the cobbled beach is so fortified that any breach is short-lived.” Though Kennedy says the elbow is relatively stable today, breaches like the one in 2011 could happen again.

A south-facing view of the Dike Bridge on Chappaquiddick. Photo by Josh Shortsleeve

The Trustees are taking steps to prepare for and hopefully prevent some areas where erosion could hit. Tom O’Shea, the Trustees’ director of field operations, discussed the process. “We are targeting areas at risk using scientific models that The Woods Hole Group applied for us,” O’Shea says. “It is not guesswork, but actual science to help us make the right moves in managing that risk.” Based in Falmouth, the Woods Hole Group is an environmental, scientific and engineering consulting organization that does a lot of work pertaining to coastlines. “We may likely need some sediment transport and sand migration studies to better understand potential future shoreline change,” O’Shea says, adding that areas currently viewed to be at risk include the Dyke Bridge and Causeway as well as marshland and trails leading to the lighthouse.

According to these models, O’Shea says there is “zero percent chance” that Cape Poge Light will be flooded due to shoreline change between 2030 to 2070—the date range used in the models. “We are the first conservation organization to use these models,” O’Shea says. “They are allowing us to be proactive and see where we might need to make adaptations. We can choose where to fortify, or to retreat [move a structure away from danger], and where to create and restore more resilient systems like salt marshes and barrier beaches.”

Both O’Shea and Kennedy agree that the use of the models could help other communities facing their own coastal vulnerability issues, and that the Trustees are available to offer their experiences if and when needed.

Chappaquiddick and the stunning Cape Poge entice and enthrall locals and visitors alike with their scenic vistas and natural wonders. The region is changing, though, and those who visit from time to time will notice them, some subtle, others dramatic. Like different areas on Cape Cod and the Islands, Martha’s Vineyard is an ever changing landscape that man is advised to both adapt to and appreciate.