The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: Great Point, Nantucket

Editor’s note: This is the 16th in a series of articles covering the region’s dramatically changing coastline. Click here to see all of the articles.

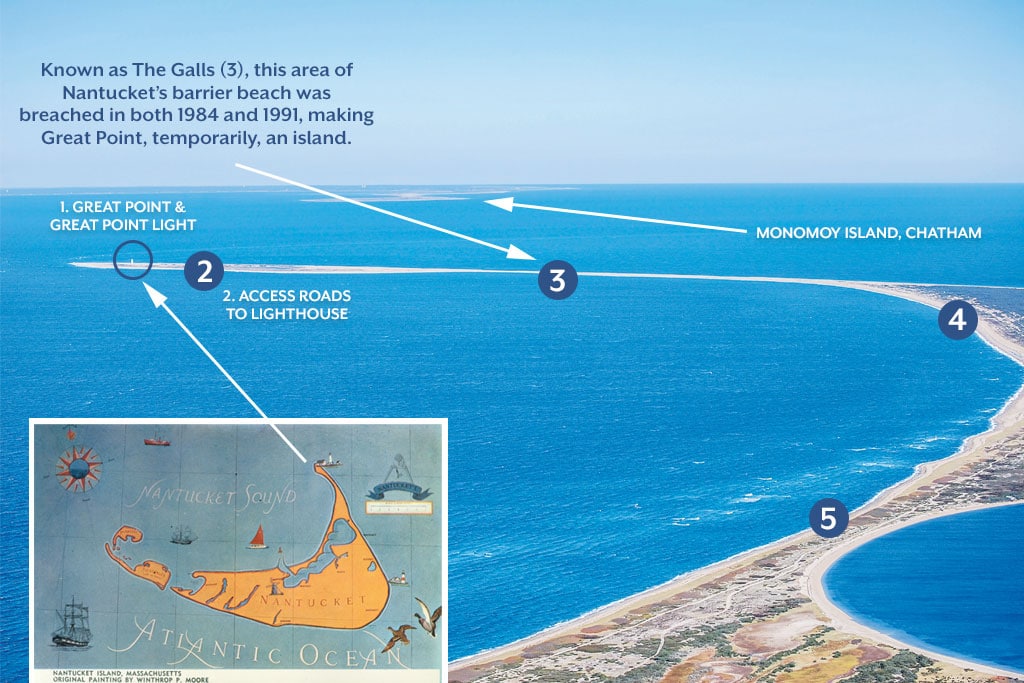

A northeastern view of the Coskata-Coatue Wildlife Refuge on Nantucket, with Great Point at the tip. The first lighthouse was built at Great Point in 1784. Photo by Josh Shortsleeve. Inset, this map of the island was painted by artist Winthrop P. Moore. Courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association

In the 18th century, the passageway between the southeastern tip of Cape Cod and Nantucket’s Great Point (1) was one of the busiest on the East Coast due to the island’s booming whaling industry. The route was dangerous, though, with strong currents and notorious shoals, and in 1784 a lighthouse was built at Great Point to help mariners navigate the passage.

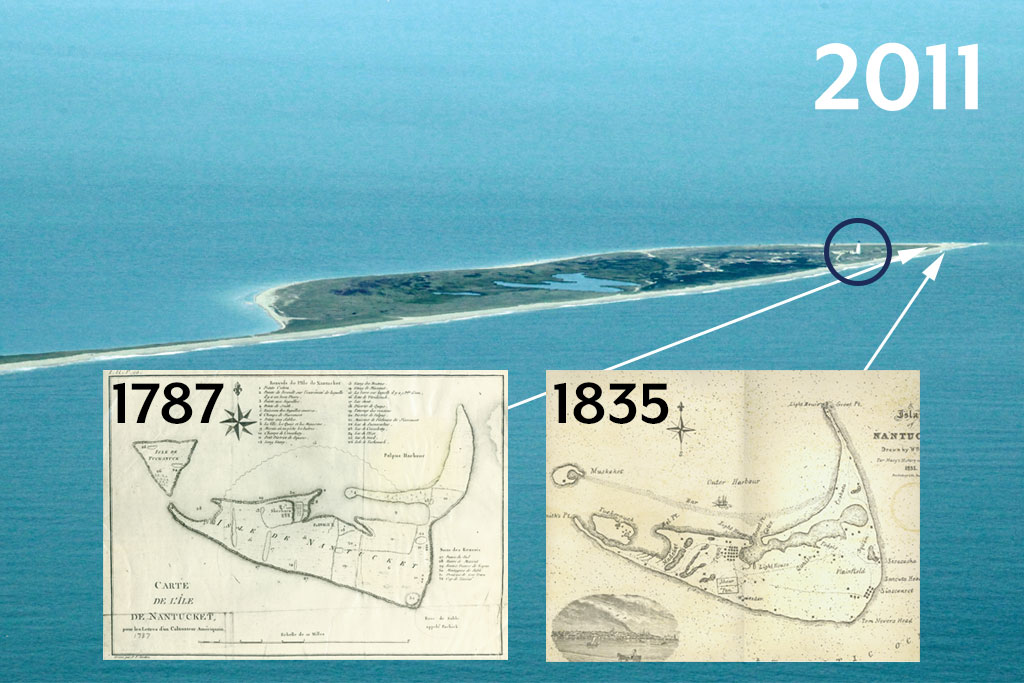

Naturally, the wind and waves that imperiled ships passing by have also done a number on the light, and several repairs and replacements have been made over the years. And Great Point itself—the northernmost tip of a long, narrow and curving peninsula that juts out like an arrow into Nantucket Sound—has also been impacted, with erosion and breach occurrences influencing its current shape and geography. In this article, we review some of the history of the lighthouse and examine how time and tide have shaped the area over the years.

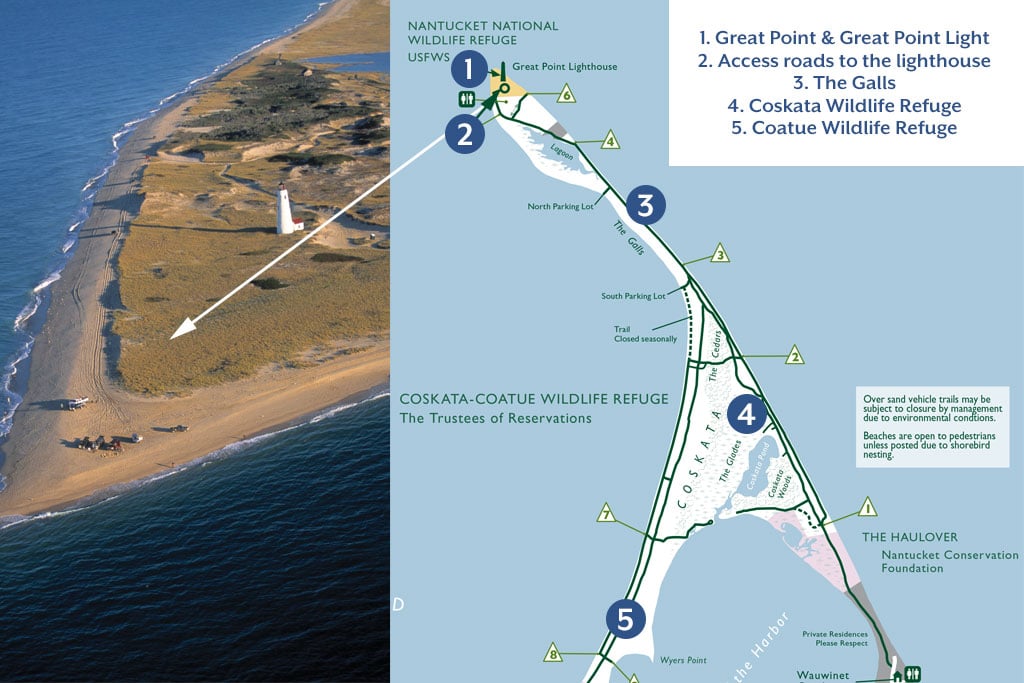

Great Point is located at the northern tip of Nantucket, just north of the Coskata-Coatue Wildlife Refuge, which is owned by the Trustees of Reservations. The 21-acre parcel on which the lighthouse sits is part of the Nantucket National Wildlife Refuge, but to get there by land, visitors must travel through Coskata-Coatue. In addition to stunning scenery, Great Point is home to seals, endangered birds such as Piping Plovers and great opportunities for fishing. The remoteness is part of the appeal. Fred Pollnac, the Trustees’ Coskata-Coatue Wildlife Refuge superintendent, explains. “You really get a sense of the power of the ocean there,” he says. “It is very exposed to the elements, and even on a calm, clear day, you still get that sense of being ‘away at sea.’”

A recent aerial view of Great Point, looking southeast. Photo by Terry Pommett Nantucket map courtesy of The Trustees of Reservations

Built in 1784, the original lighthouse—officially named Nantucket Light—was made of wood. It was destroyed by fire in 1816. A second light was built on the same spot in 1818, this one of stone. As years passed, erosion nipped away at the surrounding coastline, and the stone lighthouse kept “moving” closer to shore. By the early 1980s, the light was just 40 feet from shore, and many were clamoring for it to be moved inland. According to a 1981 article from The Inquirer & Mirror, The U.S. Coast Guard, which maintains the light with the Trustees, estimated that such a project could cost as much as $1.5 million, and that Mother Nature should be allowed to take its course. This conversation was made moot on March 29, 1984, when a hurricane-force storm toppled the 70-foot lighthouse. According to Pollnac, the storm surge undercut the light’s shallow foundation, causing it to collapse. On the same day, about one mile south, storm waters also tore through a narrow area of Nantucket’s barrier beach known as The Galls (3), making Great Point, at least temporarily, an island.

With the help of the late U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy, $2 million was raised to build a replica of the lighthouse, and on September 7, 1986, the new tower—made with reinforced concrete and a rubblestone exterior—was dedicated at a spot several hundred feet further inland. The new light was built with a deeper foundation to better protect it during storms.

Another breach took place at The Galls during the “No Name Storm” of October 30, 1991, again making Great Point, briefly, an island. Pollnac explains why neither of the breaches became lasting features. “Though that region is overwashed during big storms there is a lot of sediment transport in the area,” Pollnac says, “making it likely that any breach won’t become permanent.” Since 1991, though, Pollnac says no more breaches have taken place. In February of 2016, winter storm Olympia caused storm tides to overwash the area, though vehicles could traverse it at low tide. Today, The Galls measures 200 feet across, and Pollnac says it’s a top concern for the Trustees, partly because the light is still active and requires regular Coast Guard visits.

Like other coastal areas, the peninsula follows a natural ebb and flow, Pollnac says. “Great Point goes through a cycle of erosion,” he says. “The shape of the tip shrinks and expands. The beach gets reduced in winter and by late spring it’s built back up. It’s cyclical.”

A westward looking view of Great Point. Photo by Chris Seufert. Historical maps of the island from 1787 and 1835. Courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association

Since taking on the position in 2015, Pollnac has learned about changes that have taken place in the area over the years, and others he has observed first-hand. For example, since 1995, he says about 100 feet of beach east of the lighthouse has eroded, leaving the light an estimated 300 feet from shore today. In the fall of 2012, Hurricane Sandy carved a large dent in the dunes in the same area. And though the lighthouse does not appear to be in any imminent danger, Pollnac has observed erosion’s powerful effects elsewhere on Great Point. “One thing I saw in December 2016 was flooding of the access road near the lighthouse (2),” Pollnac says. “There is an intersection where you can head toward the ocean or sound side. A few storms came from the west, one after another and, combined with high tides, flooded the road more than 400 feet from the shore.”

That intersection—and the rest of Great Point, including the land on which the lighthouse stands—is owned by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. The agency’s role is to protect wildlife and wildlife habitats on the land it owns. According to Libby Herland, project leader of the Eastern Mass. National Wildlife Refuge Complex, an organization of eight wildlife refuges, this responsibility includes building and maintaining symbolic “fencing” (posts and string) in an area north of the light to keep seals from being bothered by humans, and fencing the nesting habitats of piping plover and other endangered birds. “Putting up fences protects the wildlife,” Herland says, “but it also protects the dunes by keeping people and vehicles off of them.”

Tom O’Shea, the Trustees’ director of stewardship and natural resources, has been targeting areas of critical concern using scientific models used by the Woods Hole Group, an environmental, scientific and engineering consulting firm. He says the models, which predict sea level rise and storm surge increases for Great Point in the years 2030 to 2070, paint a relatively dire picture for the area—but adds there is only so much anyone can really do. “We are not sure how proactive we can be,” O’Shea says. “We need to wait for more sediment-transport analysis. We want to be smart about any adaptations we make.”

Analyzing the sediment, he says, can give researchers information about where accreted material has come from and where eroded material has gone. Once the study is completed, O’Shea says the Trustees will have a better understanding of how the beach will likely change, and may decide to implement new technologies currently under development to help shorelines adapt to or withstand erosion. These include a new type of fencing that helps disperse wave energy, or the installation of oyster reefs to help the beds—which protect shorelines from erosion—grow faster.

Ultimately, O’Shea says man can—and should—only do so much. “All barrier beaches are dynamic,” he says. “It’s important to let the natural processes occur. We need to not take action unless it is really necessary.”