The Cape’s Best Public Relations Officer

Cape Cod Life / Annual Life 2015 / History, People & Businesses

Writer: Nancy White

The Cape’s Best Public Relations Officer

Cape Cod Life / Annual Life 2015 / History, People & Businesses

Writer: Nancy White

Joseph Lincoln’s prolific writing boosted Cape Cod tourism a century ago

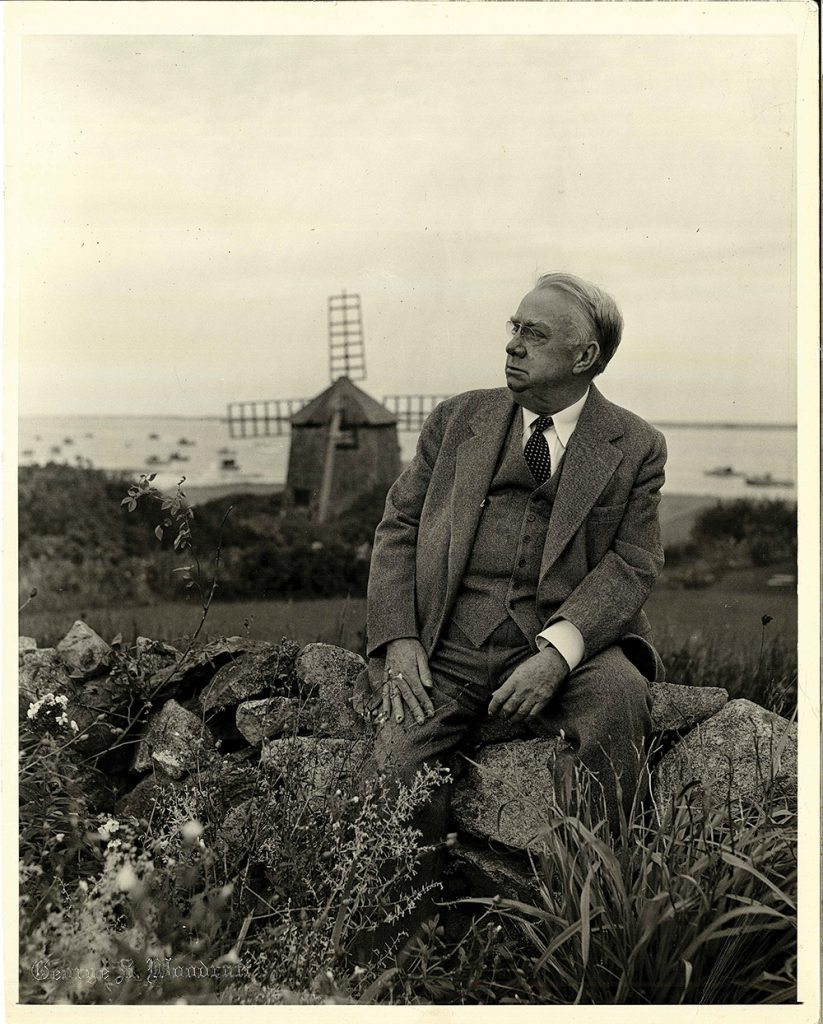

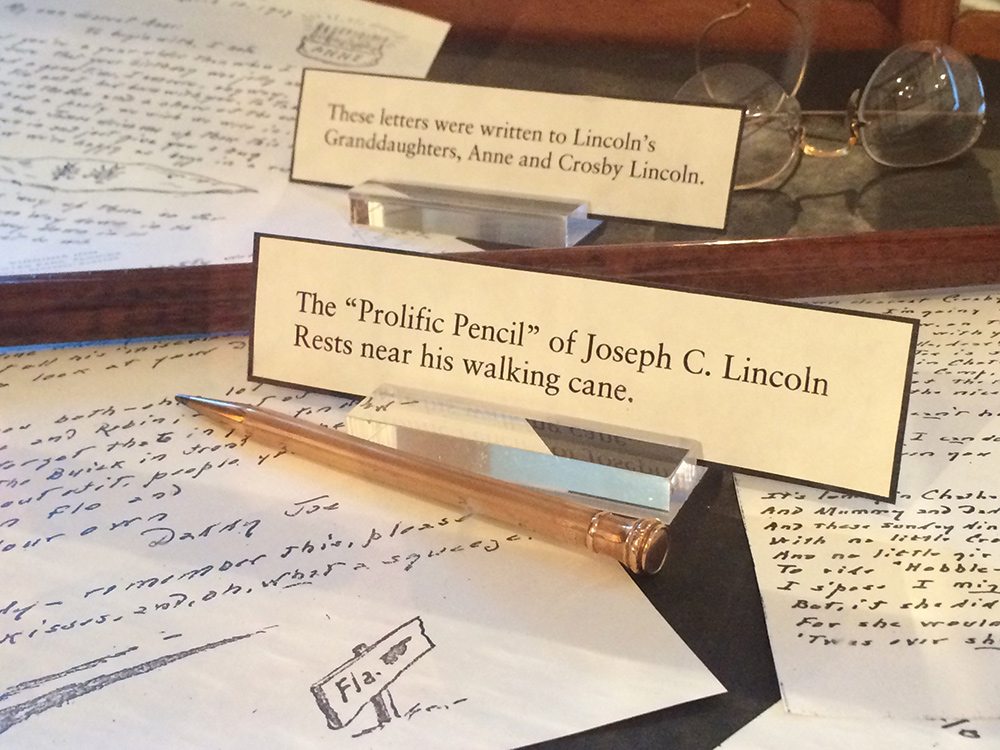

Wake up. Reach for a legal pad and pencil. Write. In the days before computers, word processors and spell check, this was the simple process early 20th-century author Joseph Crosby Lincoln followed to complete his work.

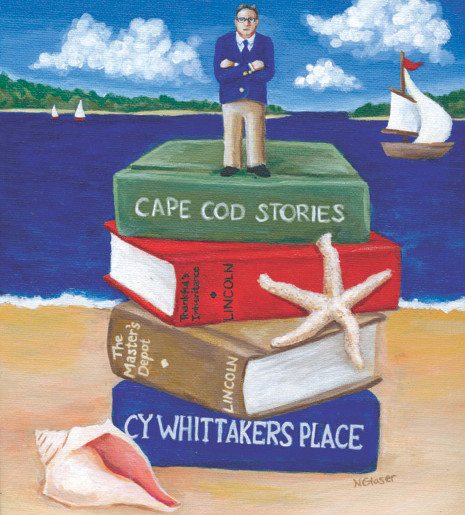

Keeping a disciplined schedule, Lincoln wrote an average of one to two books per year throughout his career, publishing more than 35 novels as well as countless short stories and poems from 1904 to 1944. His short stories and serialized novels were published in the most popular magazines of the time, including The Saturday Evening Post and Harper’s Bazaar; his books—all set in a fictionalized version of his beloved Cape Cod—introduced the coastal region to a national audience.

Artwork by Nicholas Glaser

The son and grandson of sea captains, Lincoln was drawn to the ocean and the people who made their living upon it. He wrote of quaint villages with working harbors populated by quirky neighbors who dreamt up schemes—well-meaning and otherwise. He wrote about salty sea captains, lazy men, strong women, and tony city slickers as well as out-of-town visitors who often came into conflict with these natives. The Cape of Lincoln’s fiction features towns that may sound familiar to the reader at first, but they’re just a little different from the real McCoys; examples include Wellmouth, Trumet, Bayport, Ostable and Denboro.

And Lincoln’s books always had one thing in common: a happily ever after. “If someone is having a bad day, I tell them to read a little Lincoln, it will brighten up the spirits,” says Sandwich’s Jim Coogan, a writer and Cape Cod historian. “You know within the first few pages how the book is going to end up, but you still want to read on. There’s enough complication in the plot to keep you interested and guessing.”

Lincoln died in 1944—more than seven decades ago—but his legacy in local literary lore remains strong on the Cape. His fans are scattered across the peninsula, and the Chatham Historical Society has a room dedicated to the author and his work.

Born in 1870, Lincoln spent his formative years in Brewster, where he got a fair taste of coastal life. The town was the kind of place where everyone knew one another; with a population near 1,000 at the time, it was hard to avoid one’s neighbors.

When Lincoln was just 10 months of age, his father, Captain Joseph Lincoln, died of a fever. At the age of 13, Lincoln and his mother, Emily Crosby Lincoln, moved to Chelsea, just north of Boston proper; there, he attended the Williams Grammar School through the ninth grade. “I think this had an impact on the outcome of his life,” says Priscilla Dalrymple, a docent at the Chatham Historical Society and a big fan of Lincoln’s writing. “He got a much better education, served as editor of his high school’s newspaper, but still had a firsthand, native viewpoint of the Cape.”

Photo courtesy of the Chatham Historical Society

William Moore, a professor of American Studies at Boston University, says the move north did even more for Lincoln; it instilled in him a nostalgic outlook for his childhood home, and the sentiment is reflected throughout his writing. “Joe Lincoln’s Cape Cod is of New England, not in New England,” Moore wrote in a presentation for the Chatham Historical Society’s conference on Lincoln in 2004. In an interview, Moore elaborates: The Cape Cod described in Lincoln’s books was not reality, but rather a selective portrayal of the region. “Lincoln’s novels represent the culture of the time, but he doesn’t evaluate [or critique] it,” says Moore. “His writing is for a reader’s pleasure, for a pastime.”

During the early 20th century, Americans were struggling with the trials of war, the Great Depression, and the pains of modernization. According to Moore, Lincoln’s readers welcomed the opportunity he offered them to escape to another place.

Artwork by Marcus Dalpe

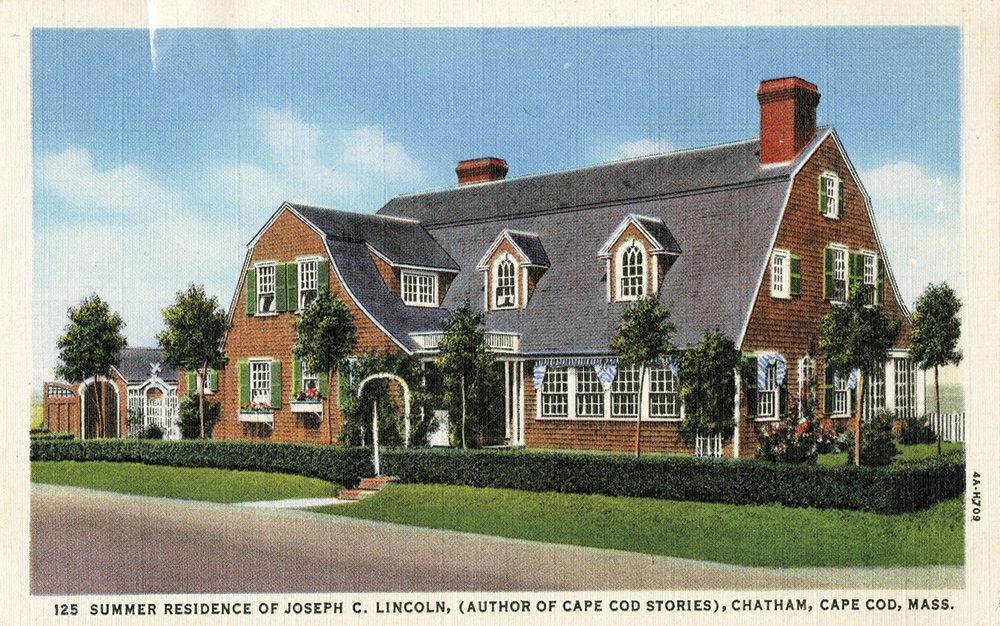

Inspired by Lincoln’s work, many traveled beyond the pages of his stories and sought out the Cape as a real-life getaway. “People came to the Cape because of his books,” Moore says. “He was the Cape’s best public relations officer. People traveled to the Cape with his books in hand, searching for characters. He codified what the Cape Cod experience would be like for tourists.” In 1916, Lincoln built a summer home in Chatham, which he called “Crosstrees.” Still located just down Shore Road from the Chatham Bars Inn, Crosstrees soon became a tourist destination itself. Coogan says the home epitomizes the Cape Cod that Lincoln wrote about: shingle-style, with gambrel roofs and porches to take in the water views.

Lincoln was one of the most successful writers of his day, selling an estimated 2 million books during his career. Remarkably, none of his novels were deemed failures, and his individual titles generally sold 30,000 to 100,000 copies. As one might imagine, Lincoln’s writing afforded him a comfortable life. He lived for much of the year in Hackensack, New Jersey—close to New York City, the heart of the publishing world; he summered in Chatham, wintered in Florida, and traveled in Europe. In 1897, Lincoln married Florence Elry Sargent, who also grew up in Chelsea.

Photo courtesy of the Chatham Historical Society

Coogan has a unique perspective on Lincoln. Born in 1944, he spent much of his first 20 years living with family in a special residence in Brewster—Lincoln’s birthplace home. As a young boy, Coogan recalls visitors stopping by to gawk at the Main Street home. “I thought they were taking pictures of me,” he says with a laugh.

In a forward to an anthology of the author’s short stories, Lincoln’s only son, the late Joseph Freeman Lincoln of Philadelphia, described his father as “short, fat, laughing, and infinitely friendly. He loved Cape Cod, people and good food. A frank sentimentalist, he believed that humans are essentially decent, and that virtue wins out in the end.” This ideology rings true throughout many of Lincoln’s novels, from his first, “Cap’n Erie” (1904), to his last, “The Bradshaws of Harniss” (1944).

Despite his success, Lincoln was not universally adored. In fact, it was the very people Lincoln wrote about who found his writing controversial. Often, readers in the small communities from where he drew his inspiration would recognize a character in a Lincoln novel as someone they knew—or knew of. “Some of the characters were thinly disguised,” Coogan says, especially if you were from the areas of Brewster or Chatham—and some resented the picture Lincoln painted.

“This made him somewhat unpopular on the Cape,” Coogan adds. Lincoln never admitted to basing any of his characters on a single person, but he did acknowledge that his characters were composites. “All of his characters are based on traits he had seen in various individuals,” Dalrymple adds. “All the names were names used on the Cape during the late 19th century, early 20th century.”

For readers not entrenched in Cape Cod life, this attention to detail added a sense of reality to Lincoln’s fictional world. “He never used an expression in his writing that he hadn’t heard himself,” Dalrymple says. “He had a wonderful way of putting things.”

In Lincoln’s 1906 novel, “Mr. Pratt,” for example, one of the supporting characters is a father of seven who refuses to work due to claims of an incurable sickness, an ailment he calls “his never-get-overs”—in other words, a disease that will eventually polish him off. Lincoln used the Cape Cod vernacular; his characters “cal’late” (calculate) and “presume likely” when expressing their opinions.

Photo courtesy of the Chatham Historical Society

In “Cape Cod Yesterdays,” a 1935 book of memoirs, Lincoln offers a humorous explanation of the many ways Cape Codders use the terms “haul” and “heave.” It is perfectly acceptable on the Cape, he wrote, to “haul” on a bowline, “heave” a baseball, or “heave and haul” bluefish from Monomoy Point. These touches that made Lincoln’s writing so distinct also made them accessible to readers of the time. “His books are so American, so upbeat,” Dalrymple says. “Of course the characters are interesting, the plots are fun, and Lincoln had a good eye for the descriptions of houses and furnishings.”

When he wasn’t writing, Lincoln’s favorite pastimes were fishing and golf, and he was a frequent visitor to the Monomoy and Eastwood Ho! golf courses. He never learned to drive—always had a chauffeur—and never attended college. He died of a heart ailment at age 74; his final resting place is in Chatham at Union Cemetery.

Today, Lincoln’s yarns, as they are sometimes called, are not very easy to come by. Many of his novels are out of print, and some of his paperback versions fetch a premium price. Local libraries, though, still have many of the writer’s novels on hand.

Despite Lincoln’s popularity, Coogan says he is not always remembered in English literature classes today; though well-written and entertaining, Coogan says Lincoln’s formulaic stories don’t rise to the level of classics. “He was,” Coogan says, “a writer of his time.”

The feeling of nostalgia Lincoln created in his writing, that which kept his readers awaiting his next novel or Saturday Evening Post installment—may still be craved by readers today. His sentiments may also serve as a reminder that not all has changed. Consider the following excerpt from “Out of the Fog,” which was published in 1940, just a few years before Lincoln’s death. “You see,” he wrote, “when summer does come down our way, the roads are a perfect jam of automobiles on pleasant days and evenings.” If Lincoln could see Cape Cod now.

For more information on Joseph Lincoln, visit the Chatham Historical Society at 347 Stage Harbor Road in Chatham.