The Wreck of the Andrea Doria

A legendary ship, a monumental collision, and a miraculous rescue operation off the coast of nantucket.

Since the Sparrowhawk sank off Orleans in 1626, the Cape and Islands have seemingly crooned siren songs to thousands of ships, luring them to destruction in their shifting shoals. While “Cape Cod Girls” may be the best known of local sea shanties, “The Mermaid” may be the most apt, with its closing lines: “Three times around spun our gallant ship/And she sank to the bottom of the sea.” One of the most infamous of these lost vessels is the Andrea Doria, which rests on the ocean floor today about 53 miles southeast of Nantucket. She sank at 10:09 a.m. on July 26, 1956, some 11 hours after a freak collision with the Stockholm, a Swedish passenger liner. Nearly six decades later, mystery continues to drive interest in the Andrea Doria—because the collision never should have happened. After all, how can two large luxury liners crash into each other on the wide-open ocean?

Artwork by Marissa Freeman

Hailing from Genoa, the hometown of Christopher Columbus, the Andrea Doria was launched in 1951. At a length of 697 feet, the ship was neither the largest nor swiftest of her day; instead, Italian architect, Giulio Minoletti, designed the Andrea Doria for luxury—and for safety. According to the 2006 PBS documentary, The Sinking of the Andrea Doria, the ship carried plenty of lifeboats and had 11 watertight compartments “meant to keep her afloat even if two were breached.” In theory, the ship could have struck an iceberg without sinking. This attention to passenger safety contributed to the ship’s glowing reputation; at the time of her demise, the Andrea Doria had become an escape for the elite, an ocean-bound Aspen—or Nantucket—whose guest lists boasted such luminaries as Tennessee Williams, Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant, Orson Welles, and Kim Novak.

Though only two lesser-known Hollywood actresses—Ruth Roman and Betsy Drake (Cary Grant’s third wife)—were passengers aboard the ship’s final voyage, the Andrea Doria’s fate drew a spotlight that would illuminate televisions across the globe for months, even years to come. On July 25, 1956, the final day of the vessel’s nine-day cruise from Genoa, the liner was bound for Manhattan at a brisk clip of 23 nautical miles per hour when, at around 3 p.m., she ran into fog near the Nantucket Lightship.

Photo courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association

Captain Piero Calamai, a lifelong sailor from Genoa, sounded the fog alert and stayed on the bridge, but, according to the PBS documentary, he “made a less cautious decision that would haunt him the rest of his life.” Calamai barely reduced the ship’s speed, dropping only to 21.8 knots. The documentary continues, stating, “the rule of thumb is that a ship should never go fast enough she can’t stop in half the distance visible from the bridge; in heavy fog that evening, visibility was extremely limited.” Speed was but one of the factors in this boating disaster, though, and not all of the mistakes made were by those aboard the Andrea Doria.

Entire books have been written about the tragedy that followed the accident, the most famous of which are Collision Course, by Alvin Moscow, and Saved, by William Hoffer. Students in merchant marine academies study the case, and over the years points of blame have shifted and evolved like the islands and channels around Monomoy. In a 2012 article for cnn.com, Samuel Pecota, a professor at the California Maritime Academy, stated, “Calamai remains a tragic, but eminently respectable figure in maritime history. He understood his supreme responsibility to the passengers and crew of his vessel and faithfully performed his duty to ensure their safety after the collision, which in his heart, he knew was largely his fault.” For years, the premise accepted by most analysts was that the Andrea Doria crew had committed the fatal mistakes, but in recent reports, fault has veered towards the Stockholm.

Photo courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association

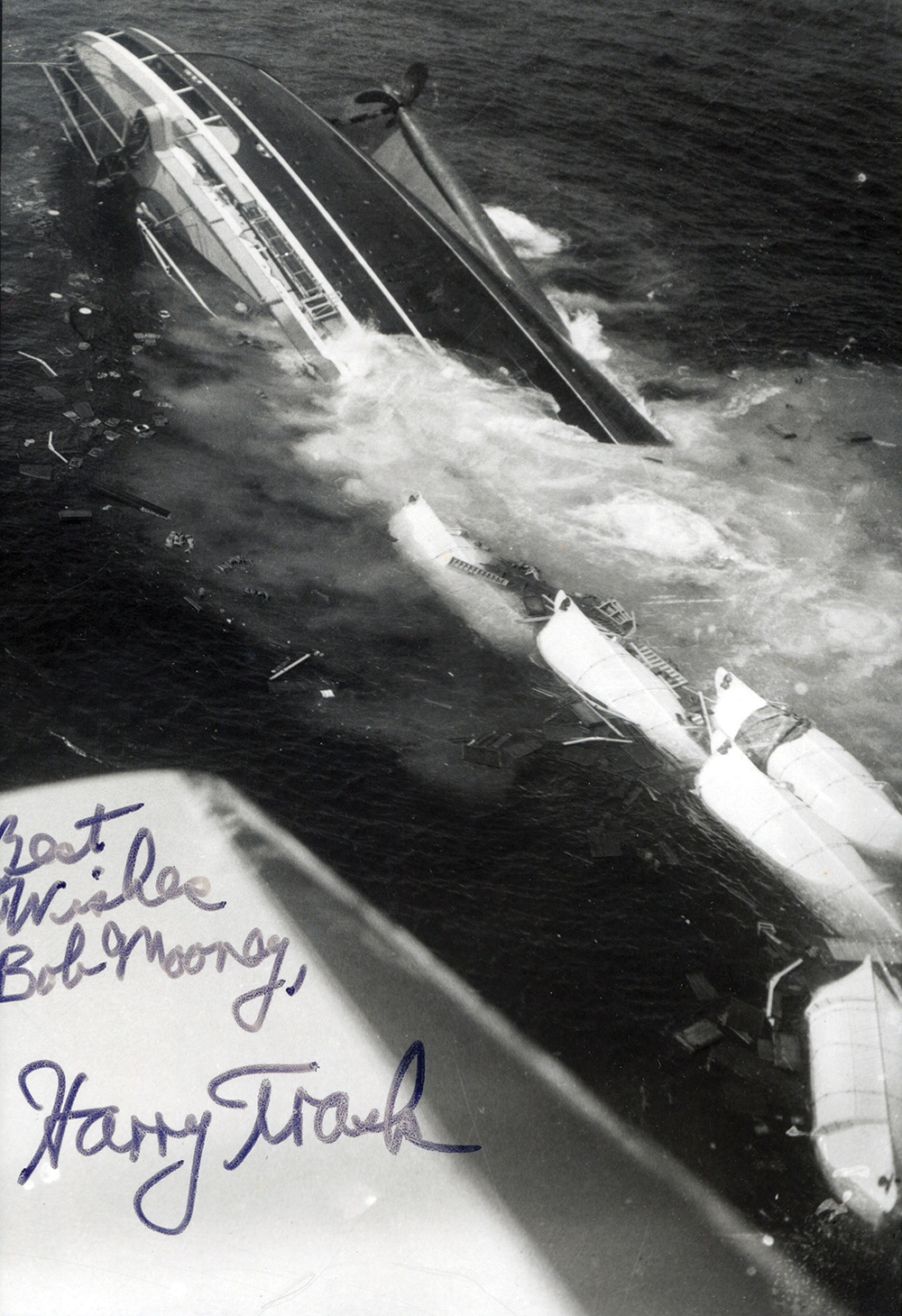

A wide range of investigators and historians has assembled a catalogue of commonly accepted errors and conditions that, together, led to the crash. First, aboard the Stockholm, 3rd officer Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johanssen appears to have ignored fog warnings. He would later misread his radar under the belief that it had been set to a 15-mile range, rather than its actual setting of five miles, making the Andrea Doria a very large object much closer than it appeared. When the ‘Doria was sighted right in front of them, Carstens-Johanssen altered course hard to starboard (to his right) without whistling a notice—almost directly into the side of the Andrea Doria. The Stockholm was built to withstand heavy ice, and thus her bow was especially tough; it tore through the side of the Andrea Doria like a knife through a soda can.

Regarding the Andrea Doria, in addition to operating at an unsafe speed, reports indicate that Calamai had failed to follow the proper procedure of adding seawater to the ship’s tanks for ballast once the diesel had been expended. According to Pecota, Calamai was operating “his vessel in a dangerously low state of stability to reduce fuel consumption.” This may explain why the Andrea Doria tipped so quickly, causing half of its lifeboats to be inaccessible. Since crew on both ships believed their passing to be ordinary and safe, neither engaged in direct communication with the other—until it was too late. Finally, as a last ditch attempt to avoid collision, the Andrea Doria altered course to port, opposite of standard shipping protocol; indeed, today’s International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea state that in head-on situations, “each [vessel] shall alter her course to starboard so that each shall pass on the port side of the other.”

Just as consensus over who is to blame for the crash continues to elude maritime scholars, survivor accounts also vary; even the number of casualties was initially in dispute. The headline of The New York Times’ morning edition of July 26, 1956—penned while the ship was still sinking—stated: “Andrea Doria and Stockholm Collide: 1,134 Passengers Abandon Italian Ship in Fog at Sea; All Saved, Many Injured.” Most reports that followed listed the death toll at 51.

Photo courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association

The U.S. Coast Guard, Navy, and the liner Ile de France, the only ship in the area equipped with enough lifeboats to evacuate the Andrea Doria’s more than 1,000 stranded passengers, responded to the sinking ship’s call for assistance. Despite pressure to deliver its own passengers on time to New York, the Ile de France played the most significant role in rescuing passengers and crew, providing the large number of lifeboats needed to make up for those unavailable on the listing and sinking vessel. The crew of the Stockholm, which had been able to seal off the ship’s crushed bow section, was also able to ferry survivors ashore. In interviews that followed, many passengers provided favorable reviews of the rescue operations, while others complained of mistreatment aboard the Stockholm, and of Andrea Doria crew members behaving both cowardly and rudely.

Dr. Lester Sinness, who had been an involved passenger aboard the Ile de France, wrote the following in 1958: “I don’t know what account the newspapers carried of the crew of the Andrea Doria, but if only half of what I heard was true, they were a complete disgrace to themselves and the country they represent.”

Years after the wreck, survivor Anthony Grillo of Brooklyn launched and maintained the website, Andreadoria.org, to serve as an online memorial and library. Grillo, who passed away in 2004, recounted: “I was 3 years old when my mother dropped me from the side of the Andrea Doria, and I landed in a blanket on a waiting lifeboat. Over the years, I would look at the scrapbook of pictures and read and re-read Alvin Moscow’s book, Collision Course . . . A website was needed to keep the Andrea Doria alive.”

Among Grillo’s archives is one recollection written by pianist Julianne McLean of Kansas, who was 25 and a passenger on that tragic evening. Her memory of the rescue stands in stark contrast to that of Dr. Sinness—in a positive way. “The crew were wonderful,” Mclean states. “The fog was very heavy and seemed impenetrable. About four or so in the morning, someone said, ‘look at that’; I bent way down and looked across the water; there was the Ile de France with every light lit, looking like a message from the Almighty! I must say that I have always thought there were a number of miracles involved with this catastrophe: First of all, the fog lifted in total darkness, around four in the morning . . . The sea was calm . . . That blessed ship stayed afloat until later that morning, allowing everyone to get off. What a tribute to the shipbuilding skills of the Italians!”

Though some questions will likely remain unanswered as the sea off Nantucket continues to wear down the legendary ship resting on its floor, Ernest Melby’s recollection—also posted on andreadoria.org—offers a sense of closure. Melby was an electrician’s mate, first class in the U.S. Navy aboard the USNS Private William H. Thomas, one of the first ships that responded to the crash site. He concludes: “The sinking of a great and beautiful ship like the Andrea Doria is an experience that no one being involved with can ever forget. The tragedy was so monumental that it seemed unreal . . . To all survivors who were taken aboard the ‘Thomas, I salute your courage and hope we treated you right on that fateful night.”

A resident of Marion, Christopher White is a freelance writer who teaches English at Tabor Academy.