Lasting Impressionism

Cape Cod Art / ART Annual 2025 / Art & Entertainment, History

Writer: Julie Craven Wagner

Lasting Impressionism

Cape Cod Art / ART Annual 2025 / Art & Entertainment, History

Writer: Julie Craven Wagner

The oldest art school in the country, Provincetown’s Cape School of Art, keeps their unique approach to painting alive with unparalleled hands-on experience.

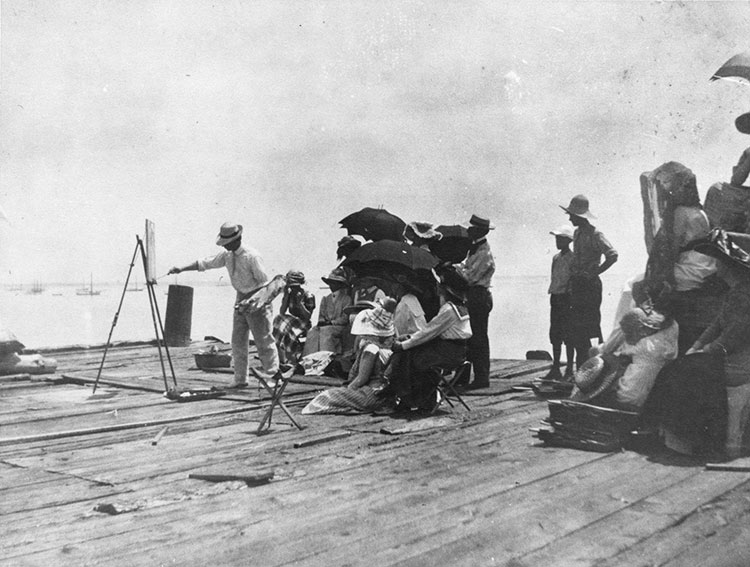

In the heart of Provincetown—where the sunlight shimmers off the harbor and the air hums with artistic history—stands a small, humble studio that has quietly become the longest-running art school in America. The Cape School of Art, founded in 1899 by Charles Hawthorne, is less a building than it is an idea—one that has survived more than a century through a deep commitment to light, color, and the act of truly seeing.

“There’s something really extraordinary about painting in the same place that Hawthorne and Henry Hensche painted,” says artist and teacher Rob Longley. “It feels like you’re part of a living history of American art.”

Longley, who studied under Hensche in the 1970s and has taught at the school for decades, now gives weekly talks that trace the lineage of the school and the philosophy that has defined it for generations. “The students love it,” he says. “We show pictures of Hawthorne, early and later works by Hensche, and examples of student work that carry those ideas forward. And then I explain how it all connects—how it’s not just about technique, it’s about learning to see.”

Painting Light, Not Things

When Charles Hawthorne arrived in Provincetown at the close of the 19th century, he wasn’t just looking for scenery. Trained under William Merritt Chase, who had studied in France with the Impressionists, Hawthorne was looking for a place where light could be its own teacher. He found it at the tip of Cape Cod, where the clarity of the air and the brilliance of the sun bouncing off water and sand created a kind of natural classroom. His mission wasn’t to teach people how to draw objects. It was to teach them to see color and light.

“He used to say, ‘You’re not coming here to paint portraits. You’re coming here to learn to see color,’” Longley explains. “And Hensche carried that philosophy forward, really deepened it. The idea is that the subject doesn’t matter—what matters is how you observe light falling on form and how you translate that into color on canvas.”

Hensche would go on to teach at the school for over 55 years, distilling and evolving Hawthorne’s ideas into a method that still defines the curriculum today. And thanks to former students like Longley, as well as others like artist Hilda Neily and a dedicated faculty trained in Hensche’s method, those ideas are still alive, taught much the way they were a hundred years ago.

No Frills, Just Truth

While many destination art schools dazzle with well-appointed studios, galleries, and fundraising galas, The Cape School of Art operates on a shoestring. But it makes no apologies. In fact, its bare-bones, plein air approach is the point.

“We’re not fancy,” says Sydney Hale, a retired airline pilot and lifelong painter who sits on the school’s board. “We don’t have a gourmet lunchroom or a slick new building. But we have the best classroom in the world—Provincetown itself.”

Hale speaks passionately about the school’s mission, calling it a rare opportunity for artists to “time travel” back to the roots of American Impressionism. “We’re out there painting five days a week, in the dunes, on the wharf, in front of the old cottages in Truro,” she says. “That’s the same environment Hawthorne and Hensche painted in. You’re not just learning art history—you’re living it.”

What the school lacks in infrastructure, it makes up for in authenticity. Teachers use a unique block study method—placing brightly colored blocks in sunlight and shadow to help students observe how natural light affects color. Students often paint with palette knives instead of brushes, not because it’s a rule, but because it forces them to focus on broad areas of color rather than line or detail.

“It’s not about the object,” Hale says. “It’s about the impression. The atmosphere. The temperature of the light. Once you get that right, the form appears.”

A Legacy Worth Preserving

The school’s small size and intense focus on one way of seeing make it a niche institution, but a powerful one. “You don’t come here to dabble,” Hale notes. “You come here to change the way you look at the world.”

And many do—often returning year after year. Some even stay to teach, perpetuating the tradition. “We’re trying to keep this alive,” says Hale. “We offer internships. Hilda is known for mentoring young painters and giving them free access to classes. One of them is now teaching. That’s how we do it—one student at a time.”

Longley, who has taken on the unofficial role of school historian, worries about what comes next. “I’m 74. Hilda and I won’t be around forever,” he says. “But we’ve got some good people—John Clayton, for instance—who are carrying the torch.”

There is no endowment, no master plan for expansion. Just a small band of devoted painters and teachers who believe in the power of light and the truth of color. For them, every canvas painted on a Provincetown morning is another link in a chain that stretches back to the dawn of American Impressionism.

“We’re teaching people how to see,” Longley says. “And once you learn that, it changes everything—not just how you paint, but how you move through the world.”

Julie Craven Wagner is the editor of Cape Cod ART.

To see work by local artists that represents the influence of The Cape School of Art, visit capecodlife.com.