A simple man, an extraordinary talent

Cape Cod Life / April 2016 / Art & Entertainment, History, People & Businesses

Writer: Chris White / Photographer: Jim Parker

A simple man, an extraordinary talent

Cape Cod Life / April 2016 / Art & Entertainment, History, People & Businesses

Writer: Chris White / Photographer: Jim Parker

Harwich’s A. Elmer Crowell—the father of decorative bird carving

Photography Courtesy of Jim Parker.

In 1874, a son of a Harwich cranberry farmer receives a gift of his first 12-gauge shotgun. He’s 12 years old, but this is a different era for fish and game hunting, when it would not have been uncommon for a Cape Cod farm boy to hunt waterfowl in his spare time. The boy learns that shorebirds are drawn to decoys; driven by necessity, he begins to carve them for himself using primitive tools such as a hatchet and a pocketknife. It’s a slower time than modern day, an age when a boy measures minutes and hours not by the screens of his electronic devices but by the size of the pile of wood shavings accumulating about his feet on the barn floor.

The boy floats his decoys on the water, he waits, and he shoots ducks for his dinner and to sell at market. As the years pass, folks notice the effectiveness of his craftsmanship; soon the boy discovers that his decoys, which he leaves set up afloat, are disappearing. No, they’re not sprouting wings to fly off with their feathered friends—other hunters have started “borrowing” them. This leads the boy to a significant innovation; he carves the birds with removable heads that he can take home in a bag. Now that people can no longer steal from him, they have no choice but to buy his work. Demand grows, and he turns a profit. Little does he know that a hundred years later, his decoys will fetch tens—and even hundreds—of thousands of dollars at such renowned auction houses as Christie’s. Nor can he know that his name, A. Elmer Crowell (the “A” stood for Anthony, though he never used it), will live on for years after his death, nor that future generations of craftsmen will consider him the father of decorative bird carving.

According to Ted Harmon, a modern-day collector of carved birds and the owner of Decoys Unlimited, Inc., an auction house based in Barnstable, Crowell would sell his most utilitarian pieces for about 25 cents each. His middle- or “challenge”-grade decoys sold for about a dollar apiece, and his top-grade “premier” work would fetch around $2. Crowell (pronounced “Crole”) would often sell his best grade birds at $24/dozen. Or he would trade them for a bucket full of quahogs.

Many of the articles written about Crowell in recent years have focused on the large sums of money that people have paid at auction for his works. It is speculated that in 2007 a pair of his birds sold for $1.3 million, though the record price for a single bird, according to Harmon, is more than $900,000. “But the money isn’t important,” Harmon says, “he is.” Without Crowell, Harmon says, others might have carved birds in decorative ways, but the art form would have taken much longer to develop. “There was really no one in the world doing what he was doing. He was decades ahead of everyone else.”

Courtesy of the Harwich Historical Society

In the spring 2014 issue of Boston magazine, Lindsay Tucker wrote, “Next to jazz and scrimshaw, decoy making is one of the few traditionally American art forms, and very much a part of the New England heritage.” European settlers learned from Native Americans how to hunt with decoys, and Harmon explains that advances in both shotgun technology and the use of wooden decoys in the 1800s created a boom (pun intended) in the market for game birds. By the time Crowell began carving his birds near the end of that century, the populations of shorebirds had begun to decline. Then, in 1918, the federal government banned market gunning with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, an early environmental protection law.

In a 2011 article for Forbes magazine titled “Ten Career Lessons From A Book About Bird Carvers,” Deborah L. Jacobs wrote, “The decline of market gunning reduced the demand for duck decoys, but Crowell saw a potential new market painting miniature birds.” In fact, this change in hunting laws would propel Crowell into the most productive and creative years of his life.

Crowell’s success as a decoy carver allowed him to both follow his passion for bird hunting and create a network of customers that would help elevate him to fame, though he never amassed great wealth. Not only did he provide customers with decoys, he also guided hunts on the Cape and in towns such as Wenham, north of Boston. Harvard professor John Phillips, an influential hunter, outdoorsman, and conservationist, placed Crowell in charge of his duck camp in Wenham and employed him for more than 10 years. Here, the craftsman would leave decoys and miniature bird carvings that caught the eyes of other well-known political and business leaders.

At the height of his career, states Harmon, “Crowell’s customers included Henry Ford, W. H. Hoover [the vacuum company founder], Pierre S. du Pont, James Storrow, Massachusetts governor Leverett Saltonstall, the royals in England, and many more.” Crowell’s reputation grew, and he was able to work fairly steadily even through the Great Depression. His full-time career as a bird carver began in 1912; he carved nearly until his death in 1952.

Courtesy of the Harwich Historical Society

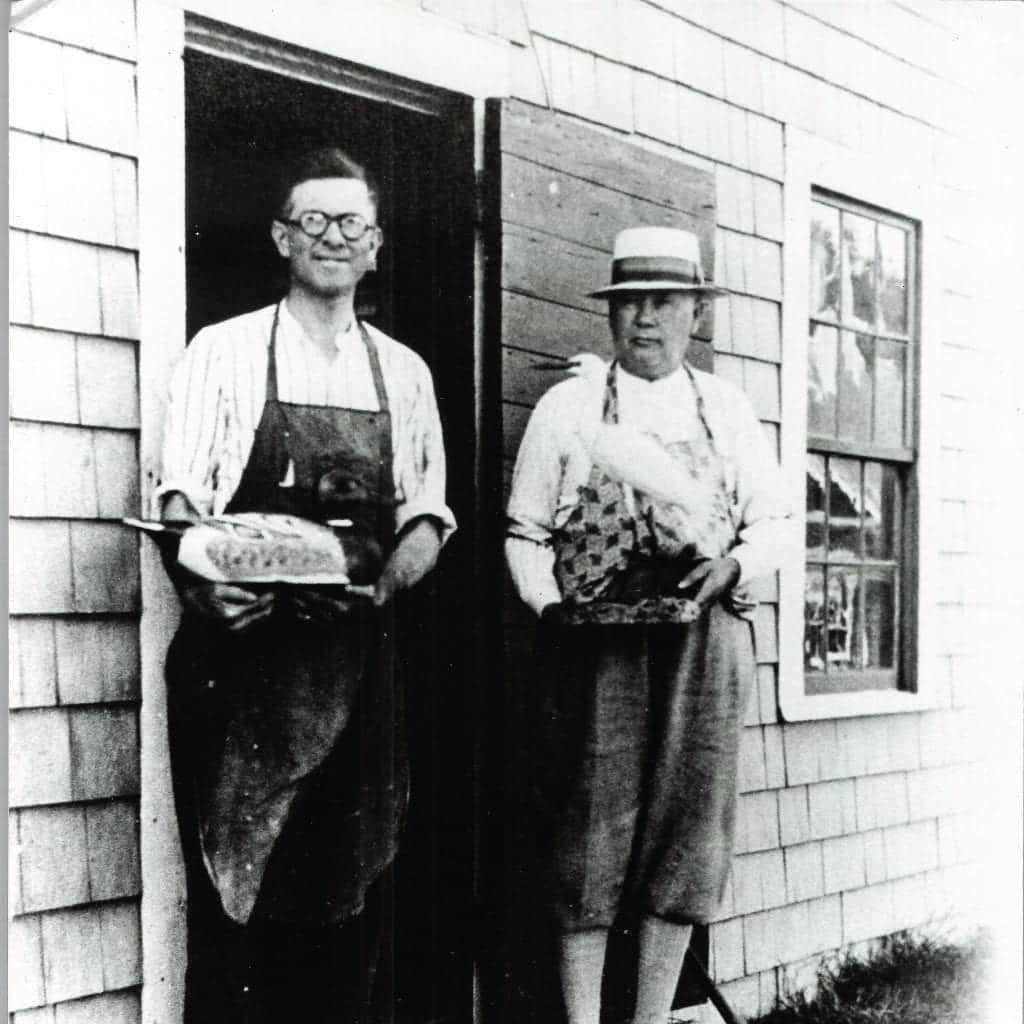

Crowell married Laura Linwood Doane, also of Harwich, who died in 1925 at the age of 56 of a cerebral hemorrhage. His only child, son Cleon, worked alongside him for many years and became an excellent bird carver in his own right. Occasionally, the father-and-son team would create and sell weathervanes or take on odd carpentry jobs. “He’d remodel a place,” Harmon says, “and give the owner a decoy as a memento.” For the most part, though, Crowell was a rare talent whose skill, timing, and luck allowed him to devote his entire adult life to his passions for hunting and carving birds.

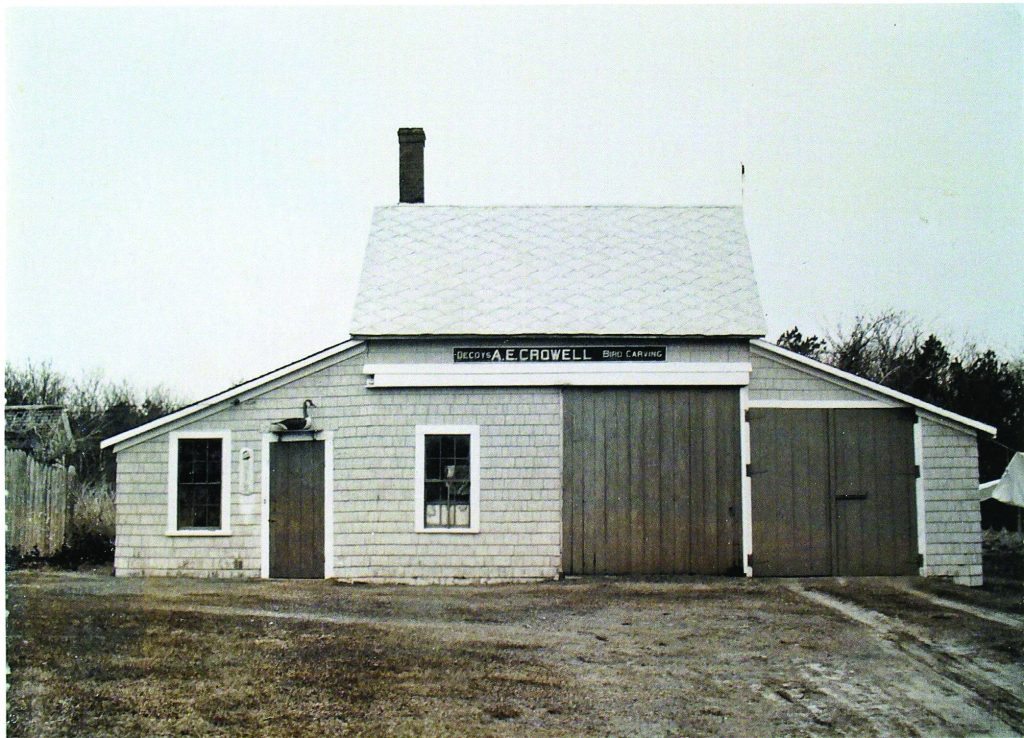

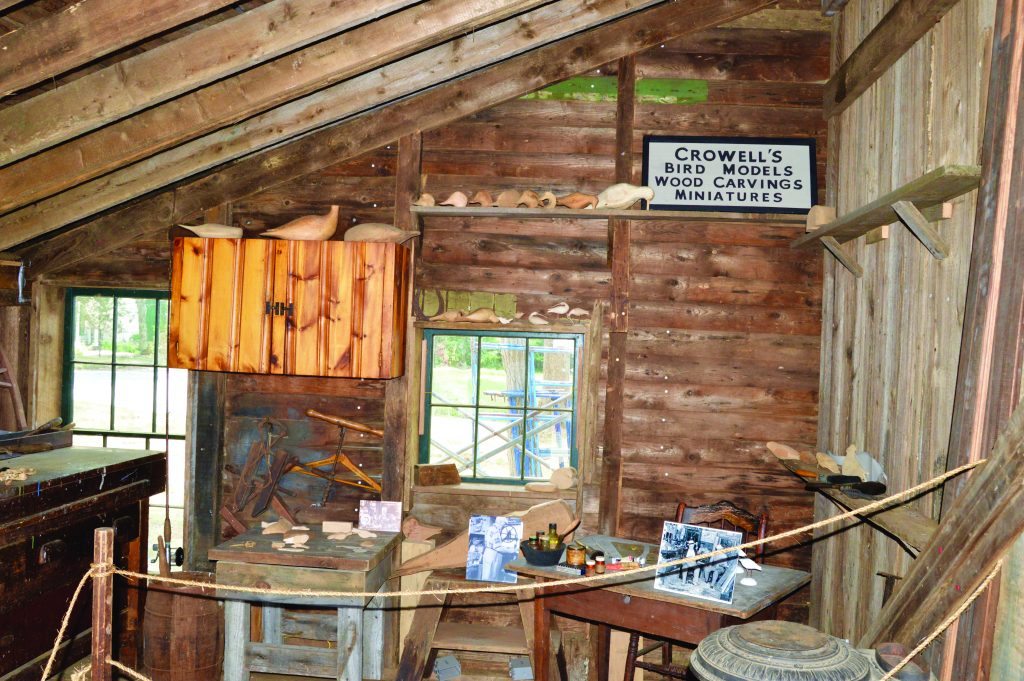

In 2005, Harmon worked to establish the A.E. Crowell American Bird Decoy Foundation, of which he serves as both director and president. “We’d love to have our own museum,” says Harmon, “but now we work with other museums and exhibitions.” The foundation’s greatest achievement thus far has been its work to relocate and rebuild the barn where Crowell carved nearly all his birds. Crowell used to call this structure his “songless aviary,” but for many years, the humble building in Harwich had been falling deeper into disrepair. “They were going to knock it down,” Harmon says. “We raised money and made arrangements to save the barn. We really got it done just in the nick of time to pull the whole thing off.”

The renovation of the A. Elmer Crowell Barn on the grounds of the Harwich Historical Society at 80 Parallel Street in Harwich is nearly complete; the workshop is open to the public from late June through early October. Many hands worked on this project, notably David Ottinger, the contractor; Patti Smith, who wrote the grant proposal; Sharon Mabile, the owner of the old Crowell homestead who donated the barn to the society; and Jim Parker. A Sandwich resident, Parker is a bird carver, a consultant to auction houses, and a Crowell historian. Of the barn, Parker says, “I took it apart with some friends back in 2008. I marked all the boards so it could be put back together.” Until 2014, the building, in its many pieces, lived in a container trailer housed in Sandwich waiting for a home. Other sites were contacted, but, Parker says, “It turned out that the Harwich Historical Society was the best place for it.”

Courtesy of the Harwich Historical Society

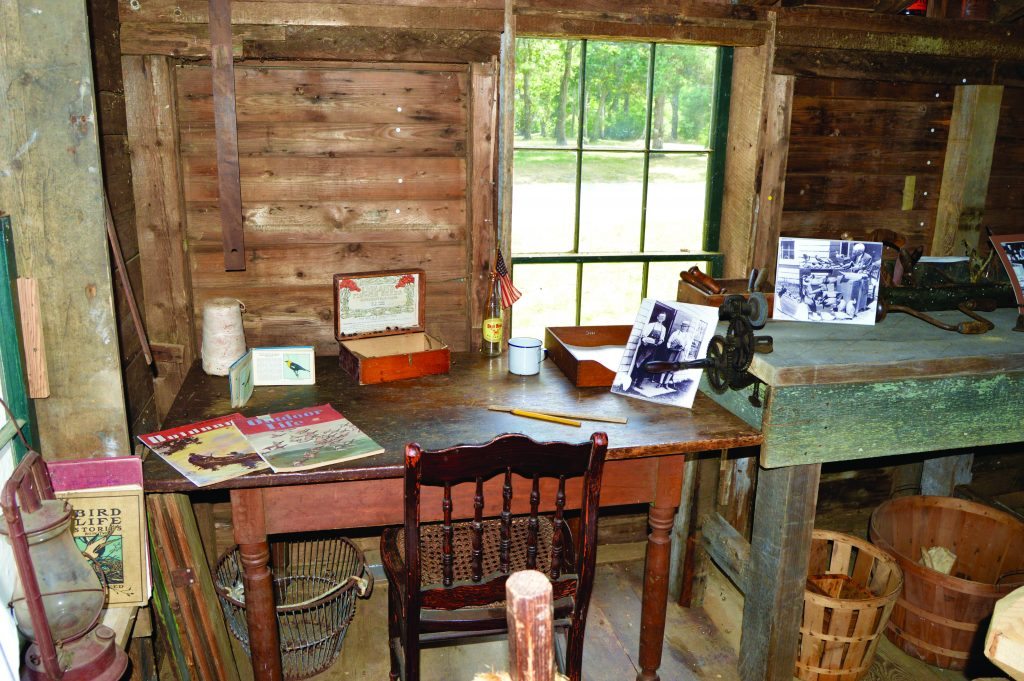

The Crowell Barn consists of a garage area, a main room in the center, and the workshop. Harmon describes the workshop as “the chicken coop where he used to carve.” The society plans to use the larger room as a museum, and to host workshops and demonstrations in the art of bird carving.

Several bird carvers and fans of Crowell’s art have made pilgrimages to the barn. “Sometimes people will come with their birds, sit on the bench, and have their photos taken,” says Desiree Mobed, the society’s former director. Parker relates a story of a woman who recently visited the barn with the Crowell carving her husband had given her early in their marriage. “Her husband had passed away,” Parker says, “but she felt good to be able to take the bird to the shop where it was carved.”

In addition to assisting with the rebuilding project, Parker has leant memorabilia to re-create Crowell’s working environment. “I had collected certain antique tools similar to the ones that Elmer used, like an old Murphy knife,” he says. “We found an old band saw that we believe is the same manufacturer and model that Crowell used.” Crowell’s original carvings are too valuable to house in the barn at this time, but the unfinished decoy and miniature bird models on display have been crafted from Crowell plans by Cape Cod artist Steven Weaver.

Juell Buckwold, a docent at the Harwich Historical Society, was a neighbor of Crowell and best friends with his great-granddaughter, Peg, so when she opens up the barn each day, she takes a trip down memory lane. “Elmer was a jolly gentleman,” she recalls. “He was kind, always had time for us, told us stories about his life or about different animals. We would often filter over to the workshop, where we played with the shavings.”

Buckwold says she never took one of Crowell’s carvings, though he offered them to her more than once. “He was a people person,” she says. “You wanted to be near him, to watch him, to listen to him. It’s wonderful he’s back in Harwich; this is where he belongs.”