The Changing Shape of the Cape & Islands: West Falmouth Harbor, Chapoquoit Beach & Black Beach

Editor’s note: This is the 17th in a series of articles covering the region’s dramatically changing coastline. Click here to see all of the articles.

Photo courtesy of the Falmouth Museums on the Green

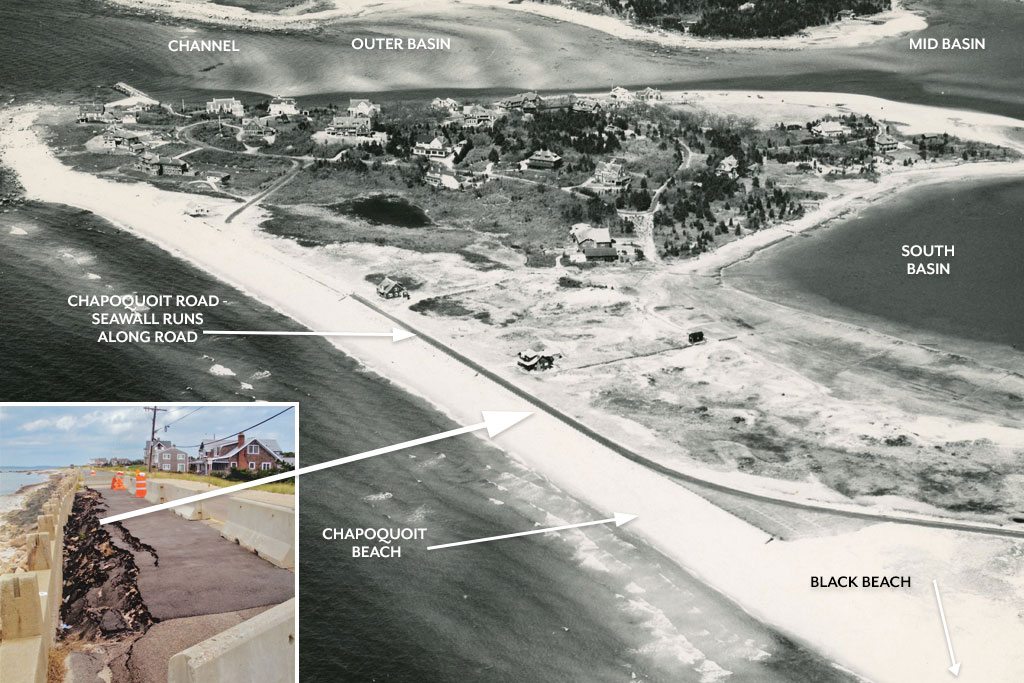

The town of Falmouth has 70 miles of coastline and a total of 14 harbors. In West Falmouth, at about the halfway point of the town’s Buzzards Bay coastline, one comes to West Falmouth Harbor, an attractive spot that sees a good amount of boat traffic. The harbor flows into a series of smaller inland harbors including the Outer, Mid, and South Basins, Old Field Cove, and Snug Harbor. The harbor has one access channel, which is protected by a 700-foot breakwater extending from Little Island at the north side of the entrance and a short jetty stretching the southerly Chapoquoit Point, commonly referred to as Chapoquoit Island.

Falmouth Harbormaster Gregg Fraser says West Falmouth Harbor is a unique spot. “It’s one of our larger harbors,” he says. “There’s a newly refurbished town pier, a dinghy dock, and a shallow draft boat ramp there. It’s also one of the few harbors in town that still has a healthy eelgrass presence.”

The harbor and the Great Sippewissett Marsh, a large tidal salt marsh to the south, are sheltered from Buzzards Bay by a 1.6-mile beach system consisting of Chapoquoit Beach to the north and Black Beach to the south. In this article, we look at how erosion and the continual movement of sediment along the coast have affected both the beaches and the harbor—and what continued loss of beach might mean down the road.

This present day photo shows the intriguing nature of the various basins, coves and points that make up West Falmouth Harbor. Photo by Josh Shortsleeve

Fraser says the movement of sediment into the channel has caused some shoaling at the harbor’s entrance and a slight shift in the navigation route in the channel. According to Fraser, the sand is being taken from the southerly beaches outside the harbor, and deposited along Chapoquoit Point’s north-facing shoreline.

West Falmouth Harbor is considered a “middle-draft harbor,” which means some deep draft vessels may face restrictions at low tide, when depths in some areas can be as shallow as 1 to 6 feet. Fraser says the harbor was last dredged in the 1960s and may be a candidate for another round due to the shoaling, but the area is also an active habitat for an endangered eelgrass, which makes securing permits for such work more involved.

Chapoquoit Beach stretches southward from the northwest corner of Chapoquoit Point for nearly one mile. According to M. Leslie Fields, a coastal geologist at the Woods Hole Group, Chapoquoit and neighboring Black Beach have been eroding at a rate of about 8 inches per year at the northern end, and 1 to 1.5 feet at the southern end from 1845 to 2014. That’s 120 feet in 170 years. Fields says the rates at the southern end are slightly higher than many places on Cape Cod. Currently, areas of the Chapoquoit Beach parking lot are just 35 feet from the water, and an area of Chapoquoit Road just north of the parking lot is even closer. Fraser says most of what might be considered “troubled areas” on Chapoquoit Beach are privately owned, so the town does not have any plans underway for shoreline armoring there.

Photo courtesy of the Falmouth Museums on the Green

A stone seawall that runs along the coastal section of Chapoquoit Road was built years ago to protect the roadway. According to Greg Berman, a coastal processes specialist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, this was done because the road is the only way to access, by land, the residential neighborhood on Chapoquoit Point. However, Berman says what was done with the goal of protecting the road is having a detrimental effect today. “The revetment is actually causing enhanced erosion,” he says. “The waves at many high tides hit the revetment, causing turbulence, which increases the wave intensity, stirring up more sediment which is then taken from the beach.” To Berman, the revetment has played a role in the gradual loss of beach over the years, leaving both of the beaches “sediment starved.”

Black Beach stretches south from Chapoquoit Beach for three quarters of a mile to an inlet, which leads into the Great Sippewissett Marsh. Berman says the beach has undergone drastic changes in recent decades. “Black Beach used to be sandy,” he says. “Portions of the beach are rockier now. The beach isn’t growing rocks—the sand is going away. The waves are strong enough to take the sand but not strong enough to take the rocks, so they stay behind.”

Berman says even without the revetments, the beaches would undergo natural erosion with waves overwashing the beach and moving sand to the upland side. He adds that natural erosion typically occurs slowly enough that the shoreline can re-stabilize itself after such occurrences. Enhanced erosion, though, means that more sand is being moved at a faster rate, and Berman says this process is currently threatening to choke off parts of the marsh.

Historic aerial view of the Chapoquoit barrier beach and the entrance to the harbor. Point to note: this photo was taken before the Little Island jetty was built. Insert: The narrow, fragile stretch of road that provides homeowner access to Chapoquoit Point is continually at risk, as seen in this photo from 2012. Photos courtesy of the Falmouth Museums on the Green

In 2015, a $120,000 Coastal Zone Management Green Infrastructure for Coastal Reliance Grant was awarded to the town to evaluate the feasibility of re-nourishing Chapoquoit Beach. The study considered using sand dredged from the Cape Cod Canal by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to nourish a 3,600-foot stretch, from Chapoquoit to a northern section of Black Beach. As part of the grant, Woods Hole Group looked at sediment movement directions and rates, and found a further study was needed to evaluate the potential for increased shoaling at the entrance to West Falmouth Harbor—as of July 2017 it had yet to be implemented. Most notably, the plan does not call for re-nourishment on the southern stretch of Black Beach up to the inlet to the marsh. Fields says the area is highly dynamic. It has undergone severe erosion in recent years, and the integrity of the dune system is threatened.

Berman says “healing” these and other beaches across the region through sand nourishment is easier said than done. “Beach nourishment is expensive,” he says, “sourcing it and getting it here.” Fields suggests that the total work involved should take into consideration the feasibility of targeted dredging in the event the nourishment project results in increased shoaling and affects navigation.

According to sources interviewed for this topic, efforts such as beach re-nourishment and the installation of revetments and other coastal armoring structures are likely to only delay or slow the natural process of erosion. Berman believes sea level rise in the next century will lead to an increased depth and extent of flooding, potentially damaging the Chapoquoit Road revetment. “There are not a lot of great answers,” he says. “There is no space to move the road landward due to development. All solutions should be done with eventual retreat in mind.”